Music and Texts of GARY BACHLUND

Vocal Music | Piano | Organ | Chamber Music | Orchestral | Articles and Commentary | Poems and Stories | Miscellany | FAQs

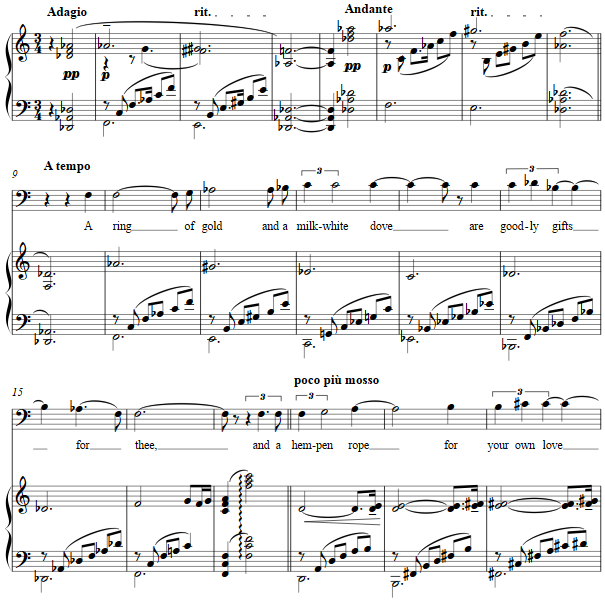

Chanson - (2015)

Oscar Wilde

for baritone and piano

A ring of gold and a milk-white dove

Are goodly gifts for thee,

And a hempen rope for your own love

To hang upon a tree.

For you a House of Ivory,

(Roses are white in the rose-bower)!

A narrow bed for me to lie,

(White, O white, is the hemlock flower)!

Myrtle and jessamine for you,

(O the red rose is fair to see)!

For me the cypress and the rue,

(Finest of all is rosemary)!

For you three lovers of your hand,

(Green grass where a man lies dead)!

For me three paces on the sand,

(Plant lilies at my head)!6 pages, circa 4' 30"

Oscar Wilde

Wilde's ordering of poems in the 1882 edition lists this text under a heading with other poems, all as "Wind Flowers."

This and other poems have been critiqued as derivative of other writers, and yet the text functions on its own merits. As to some critical voices, one reads: "Isobel Murray, in her excellent edition of the Poems, concludes convincingly that in them Wilde's attempt is 'to try on voices, to search for a voice in a tradition which is foreign to him, to perform Englishness and Romanticism as if in search of a place for his individual talent, in a fashion insufficiently assured to be described as parody, whatever mastery of parody he was to achieve in prose thereafter' (po xvi). Certainly Wilde was open in his admiration of the English Romantic tradition, and he celebrated Keats, Shelley, Morris, Rossetti and Swinburne - though not the Poet Laureate, Tennyson - in the long poem 'The Garden of Eros'. In "William Morris and Oscar Wilde," by Peter Faulkner, Journal of William Morris Studies, 14.4 (Summer 2002).

Indeed "voices" -- whether Wilde's or those he may have studied -- is an apt word. Wilde wrote: "Since the introduction of printing, and the fatal development of the habit of reading amongst the middle and lower classes of this country, there has been a tendency in literature to appeal more and more to the eye, and less and less to the ear, which is really the sense which, from the standpoint of pure art, it should seek to please, and by whose canons of pleasure it should abide always. (“The Critic as Artist,” in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde. New York: Harper Collins, 1989. This text appealed to my ear as well as eye, which alone explains the thought to set it to music.

The setting plays the two characters in differing harmonic domains, with the image of the beloved centered around D flat major with common-tone harmonic relationships, while the break with each rhythmic push into the next domain and faster tempi sets the lover's darker words beginning around D minor. The form is a simple AABA, the third strophe treated as a textural break from the earlier repetitions. The setting ends with the final D flat turning a harshly percussive, single D flat minor chord, as the voice -- that of the lover who has catalogued the many images in order to tell the tale -- repeats the clear reasoning and confession that all was done 'for you' throughout the setting was in the end done "for me!"

The score is available as a free PDF download, though any major commercial performance or recording of the work is prohibited without prior arrangement with the composer. Click on the graphic below for this piano-vocal score.