Music and Texts of GARY BACHLUND

Vocal Music | Piano | Organ | Chamber Music | Orchestral | Articles and Commentary | Poems and Stories | Miscellany | FAQs

Borrowings:

Towards a Theory of Music and the Mind - (1993)

FORWARD

Since music is created by human beings, we must regard the source, or raw materials, first of all as human facts. Roger Sessions

How does one arrive at the "human facts" [Sessions, 1950, 188] of music? Just as music theory records understandings of the ways and means by which human beings make and understand music, a theory of music might best be not only about music, but about music and the human mind.

In terms of reliable knowledge, one hopes for "a strongly predictive or explanatory theory to explain hidden mechanisms with relatively simple properties of which the observed behavior is a complex manifestation." [Ziman, 1978, 168] Music is a complex manifestation of humanity. What "hidden mechanisms" and "simple properties" might underlie it? Beginning with such questions is a productive step towards such a theory of music.

Questions about "human facts" and reliable knowledge about music cannot be answered within the discipline of music alone, but require "human facts." This monograph therefore employs elements not only from music and music theory, but also from linguistics and semiotics, cognitive psychology, neurobiology, and formalist and connectionist philosophy. Additional readings into these disciplines are suggested to clarify more fully this cursory sketch towards a fuller theory about music.

CHAPTER ONE

Overture to a Theory

Art, n. This word has no definition. Ambrose Bierce

1.1 What Is Music?

Music may seem to have a clear, concise definition, but -- like Bierce's humorously telling definition of art -- pinning down the many parameters of that definition proves easier said than done. One among life's many phenomena, music have been defined and redefined, often in mutually exclusive terms [surveyed in sections 1.3 and 1.4], such that one may question which definitions might be deemed of value and which should be refuted.

A quick reference to Cage's watershed 4'33" aptly demonstrates this conundrum. The piece is scored for performer(s) on any instrument(s) in which the opening and closing are demarked without any intervening playing. The work has been programmed, performed and published [C.F. Peters] as music; equally the work has been reviled as "snake oil," and generally abandoned in current programming (except for the infrequent Cage retrospective). Whether the work is music or not has to do with one's own definition of music. Certainly the work pushes the limits of most definitions, and incites dialogue about what music is.

A historical comparison might be made to the anguish registered against the practitioners of Ars Nova by those now identified as practitioners of Ars Antiqua. Certainly, defining music is a centuries-old yet ongoing activity. Definitions and redefinitions underlie the work not only of theorists, but of composers in many ages who by their work pursued and extended the definition of music -- from monody to polyphony, from basic harmonic structures to the broad harmonic expanses of the late Romantic symphonists, from tonality to atonality and polytonality, from culturally agreed-upon and shared structures to aleatoric, chance operations.

One contemporary theory offers an absolutist, ontologically invested calculus of music which purports to define value and greatness in musical works, thereby implying hard proof for lesser value and ignominy in other works [Meyer, 1959]. The mere act of defining music, whether through the creative work of composition or by the analytical insights of music theory, immerses one into language, logic, cultural, psychological and philosophic issues with all their attendant challenges.

One strategy in delimiting music in order to reach a definition has been to label that which is 'outside' the domain of music as extramusical. This tactic is not without grave problems.

1.2 What Is Extramusic?

If the definition of music is not easily accomplished, the inclusion of this contrasting domain makes definition yet more problematic. Twentieth-century music theory has broadened its explorations into music's mysteries is response to the diversity of music which this century has produced. Theories abound, and the vocabulary of music and music theory has exploded with new terms and methods in a mighty effort to keep pace with the changes in music.

Several theories define music by erecting this border between the musical and the extramusical, between musical meaning and extramusical meaning, as if the omission of certain phenomena and information will better serve one's understanding of music.

Pinning down the parameters of extramusic seems even more simplistic yet cumbersome a chore than defining music, but it will be argued that this tactic is both faulty and short-sighted. The proof for this argument will come via reference to standard music theory, currently recognized theories of music, with contributions from what will be found to be valuable extramusical sources. So the premise of this monograph is that music requires and relies heavily upon not only the supportive understandings of music theory, but any and all allegedly extramusical structures and phenomena which contribute to music's mystery, value, meaning and power.

In this way, music will be construed to be defined in a far broader scope than many current theories allow. Some groundwork for the argument must be made, certain extramusical ideas introduced, and a methodology made clear in order to bolster such a theory. A theory which straddles the musical and extramusical must demonstrate its utility and effectiveness in explaining music as a phenomenon, its varying individualities in creativeness, and support as rational both the teaching via theory of music and music's place within life.

1.3.1 A General View of Music Theory

The majority view of music theory is that it follows practice, and has the ability to illustrate forms and functions of musical practice by means of its vocabulary and perspectives. Historically, there is little controversy that theory has responded to practice [Mann, 1987]. Today, there is ever less clarity as to which leads and which follows in certain individual cases -- optimal examples being total serialism and computer-generated music in which algorithms formulate musical events based on relatively few input parameters.

In the last several decades, cognitive science, psychology and neurobiology have added to the dialogue about music. Music has been postulated not only as phenomenon [i.e. Pike, 1970], but as one among several faculties of mind [Fodor, 1983; Gardner, 1983; Jackendoff, 1992]. As a faculty of mind, music is seen as a mental phenomenon involving rules systems accessible to scientific and philosophic inquiry which underlie the knowledge of music, rather akin to the machine-level codes in computers. (Hence, the "computational mind" metaphor as seen in the work of Churchland [1992] and Jackendoff [1987]. The dialogue is quite accustomed to dividing music into realms of experience and its accompanying mental processes, the notations involving reading, writing and orthography, and abstract, and the notions about form and function most generally are encompassed by music theory.

1.3.2 Music Theory in Education

Over years of study, the 'complete' musician will have amassed, incorporated and incarnated all sorts of notions about music clustered under the academic catalogue's umbrella of music theory. Unlike the curricula of many other arts, theory in teaching music is used as a catch-all phrase for much of the curriculum. As an academic term, it is ubiquitous and often ambiguous due to its broad use in both the study and practice of making music.

Music theory is most frequently conducted in the medium of language, and that language is the "object language" [in the strict scientific and philosophic senses] for which the auditory and mental phenomena of music are the "objects." In academia, music theory addresses various ways and means of reading, writing and listening to music, of its analyses, and less directly its performance.

During the course of study for that 'complete' musician, it is assumed that from immersion into music theory's disciplines and many perspectives an overall theory of music will arise, coalesce and operate to the benefit of both musical practices and understandings. This music theory underpins any philosophy of music -- a theory about music. By its open and inclusive boundaries, music theory over time takes in new terms and understandings easily. A theory of music is not wholly synonymous with music theory, but does not and cannot stand alone without its firm foundation.

1.3.3 Theories About Music

While a general consensus about what constitutes music theory can be reached, mutually exclusive theories of music abound, as Schwadron concisely surveys [Schwadron, 1967, 33-34]:

"Contemporary aesthetic theories (and sub-theories) are manifold: Croce, spiritual intuition; Maritain, moral intuition; Freud, desire and the unconscious; Santayana, reason; Langer, symbolic transformation; Garvin, feeling response; Stravinsky, speculative volition; Schoenberg, logical clarity; Leichtentritt, logical imagination; and Hindemith, symbolic craftsmanship."

Further on, Schwadron adds to the terse summary Helmholtz's "pleasurable sensations" and Meyer's "norm-deviant relationships" [p. 33-34]. Theories about music are abundantly available for such a survey.

Unlike the porous borders of the inclusive arena of music theory, theories about music frequently erect hard-edged borders, staking out exclusive claims about music, excluding other views in the process.

Stravinsky's oft-cited position is noteworthy by his singular position in this century's history, and it serves to demonstrate mutual exclusivity in a theory about music.

"I consider my music, in its essence, incapable of expressing a feeling, an attitude, a psychological state, a natural phenomenon, or whatever. Expression has never been a immanent property of music. If, as is nearly always the case, music seems to express something, it is only an illusion and not reality. It is simply an additional element that by inveterate, tacit convention, we have seized and impose as a rule, a protocol. And which, through habit or unconsciously, we have come to confuse with its essence."

[cited in Monsaigneon, 1987, 84]

About this quote there is a key from Boulanger that, with a 'wink and a nod,' the statement was constructed to avoid a deeper immersion into the Gordian-knotted issues of musical meaning [Monsaigneon, 85]. Yet, the statement is a clear rejection of expressionist theory in favor of an essentialist ideology of music.

Representing another side of the argument, Meyer carries the absolute expressionist banner, stating clearly:

"Composers and performers of all cultures, theorists of diverse schools and styles, aestheticians and critics of many different persuasions are all agreed that music has meaning and that this meaning is somehow communicated to both the participants and listeners. ...it seems obvious that absolute meanings and referential meanings are not exclusive; that they can and do coexist in one and the same piece....

[Meyer, 1956, 1]

Meyer's theory argues for meaning via the expression that Stravinsky's theory calls merely an illusion. Meyer's referentialism affirms: "There is no such thing as understanding a work of art in its own terms. Indeed, the very notion of 'work of art' is cultural." [Meyer, 1989, 351] "Kunst als Kunst" is denied solidly.

Among the disparate claims made by theories of music, Cage's is an epitome of relativism, a sort of 'anything goes:'

"As for meaning, I'm afraid that word means how one's experience affects a given individual with respect to his faculty of observing relationships. I think that is rather a private matter, and I often refer, in this case, to the title of Pirandello's play, Right You Are, If You Think You Are."

[cited in Schwartz and Childs, 1967, 337]

There are grains of value and nonsense in such a statement. Value, in that observing relationships (for Stravinsky and Meyer) has been regularly associated with musical meaning; nonsense for, while it is a personal experience, we seek to share and explicate music through performance, theory, analysis and criticism. The suggestion that musical perception is a purely relative view begs all the questions about standards, shared understandings and the cohesiveness of the musical community's notions about music, as underpinned by the broad base of an inclusive music theory.

1.4 An Exemplary Exclusivity

In the jumble of theories about music which purport to lean on the bedrock of music theory, Serafine, in Music As Cognition, summarizes varying views as 1) trait, 2) communication, 3) behavior, 4) nature and 5) sound stimulus, in order to place a theory of "music as cognition" in clear relief against them. Excluded in this theory in "all such thinking that does not involve sound." [Serafine, 1988, 79] For this definition, sound includes mental images of sound, heard "internally." but non-aural materials are banned from this theoretical lexicon; these include:

"...entertainments about musical characteristics that reach the level of verbal description ("The music sounds jagged;" "This sounds like such-and-so"), conscious awareness of the compositional or performance techniques of the piece, speculations about historical or biographical matters, verbal labeling of the progress of musical events (say, moving beyond felt changes in harmony to the exercise of labeling them after audition0. Moreover, when words occur in the artwork itself, their consideration is excluded from the definition of music if it is their semantic meaning that is the focus of attention. (But words may be defined as music to the degree that it is their temporal and sound qualities that are entertained.

There a a few other stipulations in the definition. The mention of 'human' aural-cognitive activities is meant to exclude environmental and animal sounds such as traffic noise, doorbells and birdcalls that occasionally make their way into other definitions of the art form. The conditions of 'organized' temporal events omit from the musical category both random and totally serialized sound collections (as in aleatoric and serial music) that remain unorganized by the listener.

[Serafine, 1988, 79]

This citation demonstrates the lengths to which one current theory goes to systematize a definition of music as cognition. Yet all cognitions are not found in the definition, when they relate to music, and certain quasi-musical sounds (admitted to me "music" in the above quote) are declared off limits to this young orthodoxy.

1.5 The Modularity of the Mind Is Introduced

Serafine's theory introduces elements of cognitive psychology into a theory of music. Music as one form of cognition is contrasted against linguistic cognition, in an effort to demark music from language. Additionally, this theory takes care to choose terminologies by which to loosen the grip of language on music theory. An example is the use of the phrase, "pitch distance traversed," which is used in place of the common music theory term, "interval." Aside from semantic nitpicking, it is intriguing that both "interval" and "pitch distance traversed" are cognitive linguistic borrowings, not from musical cognition, but from that mental faculty which deals with spatial understandings, issues of distance, movement, and intervals by which movement and distance are understood. As cognitive science has been invoked in talking about music, a cursory survey of some elements of cognitive science is necessary.

Music is defined, in part, as a module of the mind, one among several other modules. Metaphorically, the mind is seen as comprising "mental organs" [Chomsky, 1975], mental "frames of mind" [Gardner, 1983], "modules" [Fodor, 1983], and faculties [Jackendoff, 1992]. Of these modules, linguistics terms the one for language the "language faculty." In parallel, there is posited a "musical faculty." The extended metaphor implies that this faculty is an input/output channel of the "computational mind" [Churchland and Sejinowski, 1992; Jackendoff, 1987] with the express purpose of dealing with musical structures by input, processing and output. The mind's workings are viewed as divided into specialized, discrete functions, including music, language, vision, haptic (touch) abilities, body position senses and motor faculties.

The demarcation of music as a discrete faculty for discussion is a shared view among many current neurobiologists, cognitive scientists and neuro-philosophers. Isolating music among the modules of the mind is the common territory between the exclusivities of Stravinsky, Meyer, Cage and Serafine. Stravinsky, for example, divides music from the mind functions of conceptualization and emotion. Meyer links the musical faculty to other modules, including conceptualization, emotion and social cognition in his linking art referentially to culture.

1.6 Music Theory and Multiple Mental Modules

Inclusive academic music theory, unlike the above cited theories of music, is a virtual compendium of linguistic, visual and orthographic metaphors for the description and understanding of music. Earlier, music theory was identified as obviously linguistic, an "object" language for which aural/mental phenomena are the "objects." This is a crucial distinction for, when metaphors of music theory are examined, their insights prove regularly to invoke the extramusical modules of the mind.

From this perspective, theories as evidenced by the positions of Stravinsky and Serafine demonstrate suspicion -- suspicion against the seeming incursion of other mental faculties into what is often made into rhetoric as the "purity" of musical thought, whether at the hands of composer or theorist. To that suspicion must be addressed the challenge as presented in this monograph: without the aid of other "frames of mind" [Gardner, 1983], how can one even speak about music, much less explain it and theorize about it?

Unlike the postures of many theories about music, music theory blindly borrows from the multiple modules of the mind. Pitches are described in relative terms of "high" and "low," obvious borrowings from the spatial body representation structures fed by body position senses, as output via words of the language faculty. A sound is described as "bright" or "dull," borrowing from the visual faculty. The use of numbers in metric and rhythmic perception and notation is borrowed from the abstract conceptual structures; a clear abstract construct can be seen in Forte [1978], leaning heavily on mathematical labeling. The phenomenological perspective [Pike, 1970] relies on understandings of tension and release, both borrowings from understanding provided by the body's haptic and position senses and translated through language. Foreground, middle ground and background descriptions of aural events rely on spatial understanding and metaphors.

The reductionist sound-over-time definition of music by itself is of little explanatory import, as all events are perceived over time, and the aural sense captures not only music, however one defines it, but also speech and all manner of noise, background or not. Music is simply richer than sound-over-time definitions admit in their theoretical constructs.

1.7 Jackendoff's Modular Model

A clever hypothesis for the interlocking mechanisms of these mental modules will assist in understanding the framework in which and by which to view the input, processing, reflections and outputs of the mind involving music [Jackendoff, 1992, 1-20, 69-81].

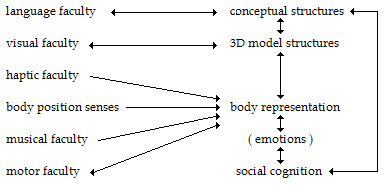

The input/output channels envisioned by Jackendoff are 1) a language faculty, 2) a visual faculty, 3) a haptic faculty, 4) body positions senses, 5) a musical faculty, and 6) a motor faculty.

Interior to these input/output channels are 'interior' modules dedicated and cross-linked; they are modules to process 1) conceptual structures (abstractions of language and logical thought), 2) 3D model structures for processing visual information and processing spatial understandings, and 3) body representations, linked to emotional responses. [Jackendoff, 1992]

Added to these 'interior' modules is a faculty of social cognition [Jackendoff, 1992, 69-81].

The sharing of input signals between these interior faculties is deemed the virtual space for meaning making and understanding, via as yet little understood computations on the lowest levels of processing and neural functioning.

FIGURE 1.

Utilizing this abstract plan, it is guessed that the input/output channels on the left of the diagram above have physically identifiable ways of of being differentiated. The structures on the right of the diagram however are theoretical constructs, no matter how accurate, and are not observable except by the artifacts of their workings.

The diagram [modified from Jackendoff, 1992, 14 and 69-81] leaves resident in the faculties on the left much in the way of processing, some relating directly to one specific sense (vision to the visual faculty) and other faculties sharing sense inputs (music and language share the aural sense, for example). The sketch is incomplete, but not for the purposes of this monograph.

Where in this model is the work of music theory accomplished? As in section 1.6, many linguistic probes borrow from both the left and right columns of the diagram. Additional examples include music theory's hierarchical understandings of large scale forms and related temporal events, captured by language in metaphors from social cognition. The graphic representations of Schenkerian analysis require spatial concepts and the metaphors supplied by the visual faculty as well, in order to 'visualize' such analytical structures [Forte and Gilbert, 1982]. The combinatorial matrices of twelve-tone theory require borrowings from numeric conceptual structures. Chironomic signs (forbearers of religious cantillation and group music making) through to the physical signings in the podium conduct of conductors rely on visual and social cognitions.

Jackendoff's model is a starting point by which to begin sketching an inclusive theory of music, without the absolutism of Meyer, the relativism of Cage, the essentialism of Stravinsky, or the reductionism of Serafine. With the model of the modularity of the mind provided by cognitive science, and with the awareness that the vocabulary of music theory implicates other modules in its metaphors, one can begin to sculpt a theory of music, including all the available materials of music theory's unbiased lexicon.

As Jackendoff cautions, what supports the rules systems of these hypothetical faculties is generally hidden to introspection; only the results of those rules systems/faculties appear as the artifacts of such systems. Thus, what are available for inspection are all the artifacts of music -- from sounds, to theory's vocabulary and concepts, scores and notations, works and performances of works, even ideologies such as the above cited mutually exclusive theories -- each artifact declared open to the domain of and exploration into music.

1.8 Extramusical Hints

If music theory has adopted metaphors from other mental faculties in order to explain musical phenomena, then one must question whether any specific musical phenomenon is in fact comprehensible without the underlying mental construct which it supports. How is foreground recognized from background in music? How is tension and release "felt" when listening to mere acoustic phenomena? How is affect, whether illusion by Stravinsky's ideology or reality by Meyer's, linked to the "sound-over-time" defined in music? Why has music historically aligned itself with texts and narratives, through words, dance, through mapping of movement onto rhythm and periodicity, and social occasions and rituals?

The terms and conditions of the few theories of music sampled above are generally ineffectual to answer such broad questions simply and directly. Yet, the Jackendoff/cognitive science model goes a long way to link the musical faculty through various paths with other hypothetical faculties, and by this construct directly moves to answer such queries. Just so, for the extramusical is posited as that by which to define music in theory.

CHAPTER TWO

Methodology and Argument

Now all this may not be so. Charles Ives

2.1 Plurality of Thought

In his text on composition, Hindemith challenges that "in technical matters there can be no secrets" [Hindemith, 1945, 6]. Yet Stravinsky posits secrets in asserting "essence." Serafine defines down music into a kind of cautious narrow purity. Are such assertions simply to be accepted or rejected out of hand? In the web of discourse which encompasses music, music theory and theory about music, many divergent views are found, in repeated attempts to delimit what music is and why it functions the way it does.

Schwadron and Serafine summarize many views about music. Additional views include music as symbol [Epperson, 1967], narrative [Barthes, 1977], allegory [Norris, 1989]. rhetoric by historical reference [Bonds, 1991] and representation [Kivy, 1991. Namour [1990] and Jackendoff [1992] endorse an implication-realization model in which expectations are built up, frustrated and fulfilled, based on the modularity of mind model [Figure 1, section 1.7]. Without comment about that model at this point, it is possible to integrate into a theory of music all the above viewpoints; it is also possible to narrowly adopt portions of the above theories or another theory.

As plurality of thought abounds within the discourse about music, the reality of their coexistence in the real world in unquestioned. The challenge is how to include them methodically into a single fabric -- an inclusive theory.

2.2 Enter Heterophenomenology

In his historical survey of theories about music, Kivy argues for music as a kind of representation. Intriguingly however, he confesses to be drawn toward an anti-representational stance, not as a matter of fact, but because that stance is "an extremely useful falsehood." [Kivy, 1991, 216] This is a remarkable admission, sacrificing ostensibly attainable ontological fact for the sake of utility. Serafine's theory agonizes over terminology, Meyer's asserts quasi-universal cultural proofs of relative value, and Stravinsky's shuns expressions in favor of essence. By their mutual exclusivities, they assert different understandings about music. Just so.

The phenomenologists of the last decades have in theory asserted that personal introspection builds a common understanding of music as a phenomenon on which agreement can be achieved. The first-person singular ["I" perceive....] exploration into the phenomenally objective and subjective facets of music, however, yields multiple and often mutually exclusive viewpoints, as above. The changing of the declension from first- to third-person singular, as suggested by Dennett, makes for a remarkable shift of position in this adventure in understanding.

Heterophenomenology [Dennett, 1991, 66-98] adopts that each position ["he" ("she") perceives....] be given equal weight. Like Kivy, the many positions are to be seen as "useful fictions." Thus Serafine's suspicions are defined methodologically to have equal weight with Meyer's affirmation of expression in music, democratically alongside Stravinsky's negation of expression as an immanent property of music. The heterophenomenological position suggests that all these theories provides clues into an overall inclusive, even liberal understanding of music.

If Kivy's and Dennett's contribution to the methodology of this monograph serves well, combined with a 'fictional' model of the modularity of the mind, then the exclusive borders of each of the above-referenced theories invokes some greater or lesser degree of involvement with the many faculties of mind, as structured in Fig. 1, section 1.7. Stravinsky's definition does not extend to the central format of emotions, as related to body representation by Jackendoff. Serafine's definition cautiously backs away from an involvement through the body representation format to the conceptual structures format, accessed by the language faculty, and so forth.

Meyer's theory reaches through the body representation format to emotional response, as do a number of other theories. For Meyer's assertion that music is culturally referential [Meyer, 1989, 351], another methodological challenge is raised. 'Art for art's sake' was the battle cry for a number of theories in the last 150 years. The balance between absolute cultural understanding and the individual, neurological bases for music is necessary.

2.3 A Borrowing From Linguistics

If the musical faculty is a mental module employing roughly the same sensory signals as language -- in its reading, writing and performance -- and if the sound-over-time definition serves both faculties albeit in varying ways and degrees, then it can be learned from linguistics, a discipline with a larger compendium of current research available to it. Certainly music theory is that object language for which music provides the object, and being conducted in language, music theory is open to linguistic exploration.

It has been noted that much of music theory's terminologies may be seen themselves as borrowings from the representations of other mental faculties and formats, as probes and tools to attempt an exploration of music mysteries. Language is an much an artifact of the language faculty, as is music of the musical faculty. In the examination of the artifacts, and by insights into their workings, the mental faculty can be seen and begun to be understood.

It is asserted that language "...is a reflection of the human mind, not just in the sense that humans have produced it, can learn it, and do speak it, but in the much more specific sense that language is as it is because the human mind is as it it." [Smith and Wilson, 1979, 265] Then music is as it is because the human mind is as it is by precisely the same argument. Natural language is defined by the concurrence of two fundamental processes: 1) articulation or segmentation, and 2) integration by which gestural segments gather into units, which themselves gather into larger units of a higher hierarchical rank.

Much of compositional technique and musical analysis proceeds by this same general bifurcation between processes. In language, single syllabic utterances are generally declared to mean very little, a phrase more, a sentence even more, and so on through larger structures. As words pile into a narrative of length, Barthes points out that meaning is not "at the end" but "runs across it." [Barthes, 1977, 87] That is, meaning eludes unilateral investigation, but requires "the long look," a view echoed by the critics [Hughes, 1990, 15]. From the linguistic point the two processes of articulation and integration are the builders and arbiters of grammar, comprehensibility, similarity and difference of meaning, appropriateness to the situation, et. al. By the very operation of the language faculty, one must segment and integrate.

Unlike Meyer's theory of music, linguistics seems firmly committed to some balance between the mental organ of language, and the cultural environment in which that faculty operates. As sister to the language faculty and as the musical faculty shares the same kinds of sensory signals, it is perhaps more useful a fiction to assert, unlike Meyer, that music is not wholly cultural; that there is "no such thing as understanding a work of art in its own terms" may deny those neurobiological similarities which are "hard-wired" in the brain. [Meyer, 1989, 351] Moreover, the tactic of heterophenomenology has declared Meyer's view a "fiction," and this model of the kinship between the musical and language faculties equally a "fiction." The remaining methodological step is to choose simply which is more "useful," in Kivy's jargon.

One theorist postulates "...all natural phenomena constitute a badly understood language." [Thom, 1975, 117] Then the "language of music" might serve as a useful fiction by that view, as well. Certainly Jackendoff's model postulates the faculties and central formats of the mind as "languages" and the posture of heterophenomenology reminds that this is fictionally useful, rather than an asserted truth.

2.4 Useful Fictions and the Language Faculty

While music theory unabashedly operates frequently in language, a number of theories about music evidence deep suspicion about the role of language in music. Serafine's distinction between words as sound structures and words with "semantic meaning" is one case in point; many parallel instances may be seen, wherein the terminologies of music theory themselves become suspect. An example may be found in the distinction between "absolute" and "programmatic" music, and the judgments which they implicate.

A caution to the musical thinker is offered by linguistics. One finds that "linguistics descriptions are not, so to speak, monovalent. A description is not simply 'right' or 'wrong' in itself.... It is better thought of as more or less useful." [Halliday, 1966, 8] A striking coincidence to the words of Kivy and Dennett. Many theories of music express a suspicion about words because they are deemed monovalent -- right or wrong. This strenuous avoidance of specificity in meaning is energetically avoided by many music theorists, and perhaps rightly so. But viewing words as monovalent does not increase the utility of a fiction, but rather limits it severely.

Words, themselves, are hardly monovalent, except in the most technical of circumstances. They are slippery artifacts of the language faculty's operation. Linguists declare words are themselves "sets of theories" about language. [Hattiangadi, 1987, 10] The language faculty struggles to create meaning, both by input and output, and that language is often ineffectual in certain instances, such as the translation of spatial cognition, as input from the haptic and body position senses, into language. [Jackendoff, 1992, 99-124] It is pointed out that in English, in comparison with the tens of thousands of nouns and verbs, there are but between 80 and 100 prepositions by which spatial information can be conveyed. Of all the rich details and range of spatial relations and cognition, most are "invisible" except in the crudest ways to the language faculty, being "neutralized or filtered out in the translation into linguistic format." [op. cit. 120]

As viewed as an organ of the modular model of mind, language best serves certain phenomena and poorly serves others. Hence, music's suspicions about language are understandable when language is viewed as monovalent and ontologically rooted. Heterophenomenology sidesteps this elegantly in avowing useful fictions, which language serves quite effectively.

Serafine's theory asserts that, in listening, we generate music. As with sound-over-time definitions, the linguist might also assert that, in listening, we generate language. The input/output channels are shared. At least fictionally, we can view music and language as close kin.

2.5 Music and Language

If music theory is in large part housed in language, such as the Harvard, Oxford and Groves embody, then it may be seen as a semantic network, heterophenomenologically a compendium of useful fictions. Some assert that music is a language, metaphorically. This becomes even more a challenge for writing yet more definitions, on the path towards Bierce's sardonic conclusion perhaps.

Adorno offers a limited view:

"Music resembles a language. Expressions such as musical idiom, musical notation, are not simply metaphors. But music is not identical with language. The resemblance points to something essential, but vague. Anyone who takes it literally will be seriously misled.

"Music resembles language in the sense that it is a temporal sequence of articulated sounds which are more than just sounds. They say something, often sometimes human. The better the music, the more forcefully they say it. The succession of sounds is like logic: it can be right or wrong. But what has been said cannot be detached from the music. Music creates no semiotic system.

"It is customary to distinguish between language and music by asserting that concepts are foreign to music. But music does contain things that come very close to the 'primitive concepts' found in epistemology. It makes use of recurring ciphers. There were established by tonality."

[Adorno, 1992, 1]

He asserts "music creates no semiotic system." As semiotics is a study of systems of signs, then Adorno postulates that either 1) there are no signs in music, or 2) there is no system in which to hold signs. As to the former, a sign is semiotically seen as a unity of "signifier" and "signified." As sounds say "something, often sometimes human," music creates signification, as a musical gesture unites with its being parsed and understood. By being "right or wrong," he postulates a system within which such values can be adjudicated. his assertion that music has no semiotic system then is symptomatic of that above-mentioned suspicion of language by music. Heterophenomenologically, his view must be allowed as neutral, however, if useful.

"Primitive concepts" akin to linguistic concepts is theorized, lending credence to some mind/brain mechanism by which pattern recognition of these primitives occurs -- in a kind of syntax, or meaning environment. It has been asserted that the musical and language faculties are kin. In Adorno's parlance, there may be found primitives, which cognitive science sees as elements of a system not defined within that system, with necessary contextual explanations or understandings which lie outside the system.

The problem of primitives [see Dunlop and Fetzer, 1992], in all the faculty domains, is that, without establishing a meaning for the undefined (i. e. primitive) sign, then that sign is altogether void of meaning. Fetzer [1991, 1992] suggests that the meaning of a primitive in a system is determined by all of its behavioral dispositions within the various contexts of the system. The primitive acquires meaning as it is used "usefully," such that the language faculty acquires not only vocabulary but grammatical rules, via Chomsky's "universal grammar" or something like it. [Chomsky, 1968, 1975, 1988; also Smith and Wilson, 1979]

The musical faculty, as a direct kin to the language faculty, may be seen to feed the central format of conceptual structures, while music feeds the central mental format of body representations. This monograph reserves its total allegiance to that architectural model, but reaffirms the model as a "useful fiction."

Music is known to operate in tandem with language, as in most choral and solo vocal music, and occasionally in this century to speech alone [i. e. Toch's Geographical Fugue]. Serafine defines away the textual considerations, though the Doctrine of Affections and music as rhetoric are historical examples of acknowledgment of such issues as textual meaning and "word painting." There seems some kind of fundamental equivalence between the domains. Seen by Jackendoff's model, language and music are serviced by similar sets of sensory input, and "hook into" interior, central formats in the mind. Rather than search for meaning individually in language or music, an "Ur-meaning" may lie resident beneath or across these systems of sound-over-time, with their visual notations and performance similarities.

2.6 Borrowings from Other Faculties

Acceding to the Jackendoff model, the musical faculty is asserted as kin to the visual faculty. Certainly much of music theory is non-linguistic and graphic. The entire notational system is pictorial, with conventional agreements about the visual representation of high and low pitches, temporal durations and the like. Just as the language faculty "operates quickly, in a deterministic fashion, unconsciously and beyond the limits of awareness and in a manner that is common to the species, yielding a rich and complex system of knowledge" [Chomsky, 1988, 157], so does the visual faculty respond seemingly instantaneously, encoding and recognizing as best it can a surrounding visual environment. Vision, not music, is the closer domain to spatial cognition. Understandings of high and low pitches are fed by notation, while high and low pitches could be also the metaphors as smaller and larger in the case of organ pipes, right and left on a piano keyboard, up and down on a bassoon, and so on.

Just as with the musical and language faculties, certain primitives must be known only by direct experience of them and their behavioral dispositions within a context. Clinically, because of case histories of patients who have suffered various brain traumas affecting vision, much is being learned about the visual faculty. In one case, the patient blind since birth gained sight via surgery. The flooding in of sense data across the retina was "frightening." [Zajonc, 1993] The problem of primitives was clearly demonstrated, as having no lexicon of behavioral dispositions for the primitives of sight made seeing, at that instant, almost meaningless, except for the emotional response of fear.

In another borrowing, music has long been associated with movement and dance. The haptic and body position sense, coupled with the output channel of the motor faculty, translate sound-over-time into physical movement. It is therefore not surprising that some theories of music reduce the definition of music to rhythm: "...an adequate definition of rhythm comes close to defining music itself." [Sessions, 1950, 3-20] But in the act of listening to music while still, the only input-caused movement from the acoustic sounding of music occurs in the minute structures of the middle and inner ear. Yet movement remains a key metaphor for music, filling much of music theory's lexicon from references borrowed from the central mental format of body representation.

Moreover often bodily responses to music are expressed through the motor faculty as various kinds of movement. One might cite eurhythmics among a number of methodologies for linking music and physical movement. So many borrowings from extramusical faculties and formats may be cited as to argue that music is interlocked with these faculties and formats in some "hard-wired" neurologically demonstrable way.

2.7 An Argument from the Model

It has been asserted that the musical faculty is a module among a number of mental modules of the brain. Moreover, this musical faculty seems to operate like its sibling modules, instantaneously and unconsciously, beyond the limits of awareness, paraphrasing Chomsky. As one among multiple modules, it yields a "rich and complex" system of knowledge , albeit non-linguistic, just as spatial knowledge is richer and more complex than language can embrace. the Jackendoff model links directly the music faculty to that knowledge and awareness under the central format of body representation, which is deemed for the purpose of this theory to be a "useful fiction."

That which is generically termed music is a potpourri of various by-products of the musical faculty. The aural events -- sound-over-time -- are taken in by the musical faculty as an input channel. The notations in scores are by-products of the musical faculty -- as output, writing via the motor faculty, and as input, via the visual faculty in reading. The notations of music theory, a sub-set of music itself, are most often input and output via the language faculty, but also carried in the orthographic pictures of certain theorists [as in Schenker; Forte and Gilbert, 1982 for an introduction], and in mathematical-logical analyses [as in the combinatorial matrices, Perle, 1962; as logical constructs, Forte, 1978]. Aside from the aural events via performing and listening, the surrounding artifacts are borrowings, embedded deeply in he multiple modules of the mind, per this model.

As to the 'sounding' of music in listening and performing, an enhanced awareness and knowledge of music is supported by those mental constructs which are provided by knowledge of music theory in its many metaphoric descriptions and conceptualizations of the organization and comprehensibility of aural events. This model borrows an assertion from linguistics:

"The fact is that is you have not developed language, you simply don't have access to experience, and if you don't have access to experience, then you're not going to able to think properly."

[Chomsky, 1988, 196]

Acquisition of musical experience is an involuntary function of the musical faculty, and, as with the language faculty, much acquisition seems to occur in the first years of life, something which is as yet not well researched or documented.

The composition of music seems a special case for this model, in that, unlike language, the creative act of composing [writing] is not as pervasive in the population as is linguistic writing. This might likely suggest that while the input channel of the music faculty is a rather well-distributed, deterministic asset throughout the species, that the disposition to output along the channel of the musical faculty is an anomalous and occasional proclivity within a given population.

This theoretical stance views Stravinsky's position as a useful explanation of the input/output channel of the musical faculty, disconnected from its linkage to the central formats of the Jackendoff model of mind. Obviously, as emotions are seen as modulated through that central format, Stravinsky's assertion of music as non-expression has limited itself, not connecting with the central formats as postulated in the Jackendoff model. But viewed broadly, music is a human phenomenon centered on the musical faculty, with vital linkages to other faculties and the central formats of the mind. Just as language services more than just words and linguistic meaning, and the visual faculty leads to an understanding beyond simple visual stimuli and 3D model structures, music seems best seen as a porous conceptual entity with the musical faculty at its core, which by lessening degrees interfaces with every other mental faculty and format.

Somewhat like Bierce's humorously intended non-definition of art, music may not be able to be defined cleanly, for the boundaries between it and other human phenomena are indeterminate and indefinite. With such a mental model as the basis for investigation, the "usefulness" of the model might be tested in exploring a number of differing problems which face music, music theory and theories about music.

That music, mapped over an amended Jackendoff model of mind, is porous, indeterminate and indefinite explains something of its mystery. Certainly the "useful fictions" inclusive stance of this monograph adopts a position that ascribes to music a richness and polyvalence which is rooted in those "human facts" by which Roger Sessions counsels us to regard music -- human facts exposed by cognitive psychology, the wealth of research into linguistics and semiotics, and the clinical realities explored by neurobiology.

CHAPTER THREE

Composition and Creativity

I certainly write music for human beings -- directly and deliberately. Benjamin Britten

3.1 Dimly Aware of the Choices

The learning of music theory is a long-term process, begun in the first years of life, alongside the eruption of the language faculty's acquisition activities. First words as applied to music appear early on, inculcating cultural as well as cross-cultural notions about music [sec. 2.2]. Much of what is cultural and perhaps all of what is hard-wired into the musical faculty begin to appear long before the music educator's curriculum comes into play. It is not surprising that, as with the language or visual faculties, foundations are laid before self-conscious awareness of them is concluded.

In "Shop Talk by an American Composer" (1960), Carter addresses "not too clearly" [his words] as he writes about music: "...many of its conceptions and techniques have become almost a matter of habit for the composer and he is only dimly aware of the choices that first caused him to adopt them." [in Schwartz and Childs, 1967, 262] The Jackendoff modular model and Chomsky's in-depth exploration into the language faculty seem to mirror Carter's conclusion, that many "conceptions and techniques" are hidden beneath musical awareness.

Stravinsky's legendary remark about being but the 'vessel' through which Le Sacre appeared echoes this viewpoint, and, of certain early works, Schoenberg admits, "I can look upon them as if somebody else might be their composer, and I can explain their technique and their mental contents quite objectively. I see therein things that at the time of composing were still unknown to me." [Schoenberg, 1975, 79] When composers acknowledge being unaware or dimly aware of the choices made in the act of composing, it may be assumed that mental faculties and central formats are operative below the level of self-awareness, at least in some cases.

Neurological research indicates in a number of mental faculties that "awakenings" occur by case history. [Sacks, 1981, 1989; Zajonc, 1993; also see Dennett, 1978; and "Mind Quakes" in Hofstadter, 1979] A coming to awareness seems developmental over time, and the musical faculty has not received the research attention that the language and visual faculties have. An anecdotal awakening is recorded by Toch: "After having copied three or four [Mozart string quartets] I became aware of the structure f the single movements." [Toch, 1977, iv] Awareness is a kind of pattern recognition indicating the size of patterns being recognized. Toch admits to becoming aware of structure -- of pattern.

3.2 Pattern Recognition

It is asserted that in science "inter-subjective pattern recognition is a fundamental element in the creation of all scientific knowledge." [Ziman, 1978, 44] The scientist is purported to have "learned to see, under the influence of the accepted paradigm of his subject." [op. cit. 50] The Jackendoff modular model of mind avers that the faculties in connection with central formats operate to distinguish pattern, in varying forms of input and varying representations of mind. They distinguish pattern because they must, by their very own nature. The hard-wired interfaces go a long way to explicate commonalities between individuals, which are more than culturally agreed-upon conventions, but rather are rooted in the innate features of the faculties' and formats' operations themselves. [see Zajonc and Markus, 1984, 73-102]

Chomsky's Universal Grammar, posited in the language faculty [Chomsky, 1975, 1988], seems to operate on linguistic primitives, recognizing their repeated use and behavioral dispositions [Fetzer, 1991, 1992] and encoding the patterns into a lexicon which itself broadens the acquisition process. Mistakes can be rampant, and yet the utility of the patterns, behavioral dispositions and resultant lexicon measure the effectiveness of the grammar. [Compare to sec. 2.2]

The musical faculty is proposed to be somewhat like the language faculty [sec. 2.5]. As with the growth of language in an individual, the musical faculty is assumed to recognize patterns in musical primitives, noting their repetitions and behavioral dispositions, and encoding those patterns into a musical lexicon. The lexicon [per Barthes, 1977] is that which corresponds to a body of practices and musical beliefs. Musical primitives seem to be differentiated from language primitives beginning in very early childhood, and crude awareness of what constitutes music seems to form before, or at least, alongside awareness.

3.3 Musical Practices and Musical Beliefs

Carter challenges that "conceptions and techniques" become a habitual practice of the composer, and that re-examination of their adoption into use is appropriate. The musical faculty, by this model, seems to have concluded many underlying musical beliefs, in part because of the mechanistic features of the faculty itself, and in part because of the musical environment which provided the faculty with a range and variety of primitives.

It has been asserted that music, limited by whatever definition of it is adopted, borrows for its supporting music theory from many ostensibly extramusical faculties. Thus, in paleo-linguistic fashion, many underlying beliefs reside in the metaphors by which music is explained in theory. Carter contends that resident, lexical conceptions and techniques are utilized by the composer without much awareness of why the conceptions and techniques are employed. The Jackendoff model, fictional as it is deemed to be, is useful in validating Carter's observation. The musical faculty is seen to be partly hard-wired and partly cultural "software," in the metaphor of computer science.

The distinction between cross-cultural and cultural facets in one's musical lexicon implies that not all "conceptions and techniques are subject to introspection and perhaps even control. Recall Stravinsky's Le Sacre admission, and Schoenberg's confession [sec. 3.1]. That which is called creativity in the composer may be hidden partially in the deep mechanisms of the individual's musical faculty, and not subject to the scrutiny of an academic curriculum. And yet music theory's broad and inclusive discipline is there to support any and all understandings as composers define and redefine music in the very act of creating it.

The practices and beliefs instantiated into the musical faculty are declared to be non-linguistic by degree, though linguistic elements are declared by this theory to be included as necessary for whatever musical purposes are defined by the composer. Hindemith charges that there are no secrets in technical matters of music. Thus such descriptions as "mysterious" and "irrational" are useless in explicating a theory of music. Their use often reflects a cultural bias against non-linguistic thinking, and the Jackendoff model structurally identifies many faculties and formats of the mind which are not language.

As cognitive psychology and neurobiology penetrate deeper into the mind's architecture, certain hard-wired musical mechanisms may be explained. Certainly, musical thought is based in pattern recognition, and parsing of music into segmental divisions and restructuring into conceptually manageable wholes [sec. 2.3] seems hard-wired into the brain. Thus, while "dimly aware" of habits of composition, the composer is obligated to work within the mostly non-linguistic elements of music in certain ways defined by the hidden and quite natural mechanisms of the musical faculty.

Thus Cage's 4'33" stands at the absolute border of music, as defined not in ideology but in anatomy and the nature of the human organism's musical faculty. Cage attempts in this piece to frustrate a general definition of music by challenging what music is, as noted in his statements about "music" which occurs around the auditorium when the piece is not played though performed. The definition that music is any and all sounds radically restructures the Jackendoff model.

3.4 Psychological Constancy

The crafty syllogism offered by Cage via 4'33" is highlighted by the Jackendoff model. Music, like language, links to other mental modules by certain formal, mechanistic principles, some innate to the organization and some culturally specific. The mind as an organizing and meaning-making entity reaches out by pattern recognition mechanisms to contact the external world. Jackendoff asserts that "whenever a psychological constancy exists, there must be a mental representation that encodes that constancy." [Jackendoff, 1992, 5] Cage plays with this fundamental psychological constancy, but is not alone in that tendency to confuse metaphors and modules of mind.

Cross-modular understandings have often been expressed, very unlike the "purely musical" stance of some theorists. In the concluding chapter if Kandinsky's Concerning the Spiritual in Art, this co-founder of the "pure" abstractionist movement in painting speaks of musical metaphors such as a visual composition being "melodic" and in the more complex forms "symphonic...." He writes about "complex rhythmic composition, with a strong flavor of the symphonic...." He allies painting with music: "The mind thinks at once of choral compositions, or Mozart and Beethoven." [Kandinsky, 1977, 56-57] Other examples from poets and visual artists can be cited, in obvious demonstration of the mixing of metaphors wherein the non-musical artist 'pines' for a more "musical" technique or method with which to create non-musical art.

By the Jackendoff model, Cage's borrowing from the format of social cognition is simply inconstant with the basic hard-wired features of the musical faculty. The model declares that when a musical constancy presents itself there will be a musical faculty representation that encodes that constancy. These constancies are recorded in the many understandings of music theory. The composer is obligated to work creatively within the constraints of those musical constancies, with primitives and their behavioral dispositions within the contexts in which they can be organized.

One such large constraint is pattern recognition. The composer works with various strategies -- the creation of a memorable music object, direct repetition, indirect reference by shared affinity (such as the sequence), contrast followed by restatement, and techniques of variation and development of features of the original object. Many schemata for accomplishing this are recorded in music theory as compositional techniques and conventional historic forms. In part, such strategies instantiate the psychological constancies by which the musical faculty functions.

3.5 Interactive Faculties and Composition

"Of course, systems interact," linguistic theory asserts. [Chomsky, 1988, 161] The musical faculty is entwined with other mental faculties and formats, according to the model [ sec. 1.8, 2.5 and 2.6 ]. Music wraps with physical movement in dance, with linguistic narratives in song and musical theater works, and with forms of social cognition. Some judgment of the appropriateness by the composer underlies compositional choices.

The composer of music to texts relies on some interpretation of that text, of scansion and syllabic stress, rarely violating the stress and clarity rules of the language faculty. The composer of theater works invests compositional strategies and details into musical characterizations. Music composed for specific social functions reflects the circumstance, ideology and venue more frequently than not.

On another level of composition, musical objects are manipulated in structural, architectural and narrative schemata of other faculties and mental formats. Music theory records these in its terminology, i.e. the symphonic "argument," the "cyclic" return of thematic materials, "cadences," the spatial metaphors of musical "sections," are a few of the many examples.

The composer works in a medium of non-linguistic thought, yet the language faculty serves music. Music is spoken of as virtual movement served by the haptic and body position sense faculties. The hierarchies of thematic materials and sections rely on concepts of social cognition. Music, in the broader definitions, exhibits emotional expression, also through the body representation format of the Jackendoff model. With Chomsky, and of composition, the model agrees that systems interact.

3.6 Encoding, Encoding Errors and Creativity

The detail of the Jackendoff model [Jackendoff, 1992, 14] suggests [by the direction of the arrow] that the musical faculty is an input channel, for the language and visual faculties are represented as input/output channels, by comparison. Figure 1 [sec. 1.7] reflects this detail. The text of this monograph has ignored this detail, but noted that the musical faculty might be seen as an input and output faculty, sharing so many features with the language faculty [sec. 2.5]. The utility of the heterophenomenological approach grants these two differentiations neutral and equivalent status, pending testing their usefulness.

The musical faculty, and in like manner the language and visual faculties, acts on inputs to recognize patterns, encoding them into mental representations upon which the central format(s) may act, according to the model. The encoding is itself a translation, in the case of music from acoustic signals to neural patterns to metaphoric understandings. The neural encoding occurs in an electrical form of charges -- ons and offs, somewhat akin to the binary operation of a computer chip; it should be noted that, unlike the serial processing of a simple chip, the computational model of mind posits a massive parallel processing by multiple mechanisms.

Ideally, the encoding of a musical object is accurate. The object is recognized.

Of composing a musical idea, Stravinsky says "I am aware of it as an object" when "satisfied by some aspect of an auditive shape." [Stravinsky and Craft, 1958, 15-17] This is a judgment of the object's character, memorability, potentiality to be received via pattern recognition mechanisms. Music theory's terminology allows the examination of musical objects on varying levels of hierarchical organization.

After becoming aware of the musical object, the constraints as noted in section 3.4 become operative strategies; the object becomes a sign, a primitive in the context of the composition, and it will be displayed/ employed through various behavioral dispositions via the noted strategies. This is a prime function of the musical faculty, as the model emphasizes.

The encoding of that musical object places it in the musical lexicon, for later comparison and reference. The manipulation of the object via the conceptual and technical skills of the composer create the contextual texture for the musical objects, a kind of non-linguistic syntax with musical meanings defined by context and use.

Schoenberg's remark about explaining features and techniques in a composition of which he was unaware "at the time of composing" indicates that much of the encoding, during the creative act of composition, is in fact hidden from introspection [sec. 3.1]. Thus a response to Carter's observation is that some choices are not "adopted" but rather are brought into being by the interaction between the innate features of the musical faculty and the cultural/ideological features of a surrounding musical environment. Some compositional activities are available for review and introspection, and some patently are not. This is not a strong allegation raised through the model, that seems to imply the "mysterious" in music [sec. 3.3], but in fact the model is instead underpinning that which this monograph has called non-linguistic thinking.

Rather than mystery as an immanent feature of the musical object, the admissions by Stravinsky and Schoenberg indicate that mystery may be unawareness, in that Schoenberg later claims to have become aware of that which he was not during the activity of composition. A lack of analytic awareness does not imply mystery, so much as involvement in non-analytic, non-linguistic thought -- that the frame of mind in which the composer seems often to work.

If accurate encoding of a musical object places the object into a musical lexicon, such as a theme or motive upon which the composer's attention, creativity and techniques are applied, an inaccurate encoding of a musical object or understanding clearly affects the mechanism of the musical faculty, as both input and output device. How might the model predict the outcome of inaccurate encoding, with the methodology and stance of "useful fictions," rather than ontology, underpinning the model?

In any historical era of music, there are certain common practices. Indeed the music theory term for several centuries of Western music is the "common practice" era of tonality. Atonality, in this century, creates a similar set of conventions -- a kind of avant-garde orthodoxy. Yet between Mozart and Haydn, between Schoenberg and Berg, between members of similar "schools" and periods, there are encoding errors, in the non-pejorative sense, which differentiate the compositions of different yet similar composers. That is, the musical faculty operates according to the subtle and not-so-subtle differences in encoding and lexical mechanisms, such that "misunderstandings" create new and novel musical objects and contexts in which those objects evidence their behavioral dispositions.

The theme and variations scheme is a by-product of this facet of the musical faculty. Of course, the standard theme and variations strategy can be found throughout the literature of many eras. In examining the variations composed to non-original themes (specifically trans-eral), the "errors" (fictional and non-pejorative) in encoding allow for the new and novel variation to illustrate differing understandings of a musical object. The model allows, by encoding errors and unequal lexicons over individual and period, for creativity and style change to be explained through both innate mental mechanisms and changing cultural mechanism as well.

An insight to encoding errors comes from Stravinsky: "...the act of invention implies the necessity of a lucky find and of achieving full realization of that find." [Stravinsky, 1947, 54] Additionally, he claims that "an accident is perhaps the only thing that really inspires us." [op. cit. 56] The accident --the lucky find -- is what the model views as the encoding error. Such errors make for an enormous range of musical creativity and expression, and are endemic to the mental mechanisms by which they are encouraged. This the "mystery" of creativity, by this model, is in fact that one cannot be otherwise. It is only in "achieving full realization" of encoding errors, in Stravinsky's words, that qualitative differences are found between individuals and creativities.

3.7 Errors and Pattern Recognition

If encoding errors within the mechanism of the musical faculty (and its interfaces with other faculties and formats0 begin to explain creativity, the errors themselves must be constrained by the limits of the pattern recognition mechanisms. For example, if a specific musical theme undergoes many differing and lexically referenced changes, then the pattern recognition mechanisms "follow" the changes and create contextual understanding for the change [sec. 3.4] which are housed as lingua-conceptual definitions within music theory. If that same musical theme undergoes massive encoding errors, it is likely that the link to the original appearance will be ignored by the pattern recognition mechanisms, and the resultant object will be defined as different and unrelated to the original. Such are the systemic constraints upon errors.

(A linguistic comparison is useful to demonstrate this: "thole" is a word in English, though perhaps obscure to many English speakers. Some anagrams of the word might be judged also words, "ethol," but constraint rules of consonant order predict, without a doubt, that "tlheo" cannot be a word.)

Because the vitality of constrained errors in the encoding of musical objects and of the strategies for their display, music theory admits to being partially incapable of expressing accurately the vagaries of music. That is, music theory can only approximate musical understanding. "Statistically defined, 'general practice' is pure fiction," Rosen writes. [Rosen, 1980, 6] Music theory then is a system of useful fictions, linguistic, orthographic, numeric and logical, which has value in its utility to translate music into conceptual structures in parallel with the musical faculty's products and processes. Specifically for the composer, it is a bi-directional relationship.

In the act of composition, invention (Stravinsky's "lucky find") is a creative ("accidental") encoding function, unique and individual. The application of common compositional strategies [sec. 3.3, 3.4] is a culturally expressed behavior. By this model, these two features of composition are not separate aspects of the process, but rather more like opposite ends of a common fabric of musical proclivities, the intensely private, creative at the one end, and the shared behaviors at the other.

The model has asserted that these above-mentioned musical proclivities have innate roots in the neurological foundations of the mind in general, and the musical faculty in specific. Additionally, the model suggests that these same proclivities are rooted also in social and historical realities of culture over time. Musical creativity and the many styles and expressions of composition are in part hidden from introspection [sec. 1.7, 3.1], and also in part codified into the entire scope and range of music theory.

Whether music is defined as limited to the aural event, or to the domain of the musical faculty, or includes the artifacts of interfacing with other mental faculties and formats, the model offers explanatory utility to each definition in an inclusive manner. Specifically, the model adapted from Jackendoff, offers explanatory utility to the composer, with verification of Stravinsky's and Schoenberg's commentaries, and a vision that it is in the constraining mechanisms of the musical faculty of the mind that both creativity and technique are anchored.

3.8 Music Is Extramusical

It is obvious that music merges with language in musical works. Music merges with physical movement in dance. Emotional responses are often ascribed as valid reactions to music. Music underscores film. Music is a multi-use human phenomenon. In its explication, music relies on multiple faculties and formats of the mind -- the visual and language faculties in reading and writing, the haptic and body position sense in feeling and expressing -- and on central formats for understanding of structures and hierarchies.

Composers such as Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Carter and Toch describe encoding errors, a lack of full awareness in the process of composition, of coming to an awareness, and of struggling to understand the underlying processes, creativities and constraints in the act and art of composition. This model provides a common model for their observations. Stepping aside from ideological claims about music, this model attempts to root an understanding of music and its composition in current research into the nature and structure of the mind, and the stance of this model is inclusive, in its claim that all the understandings about music are best understood as "useful fictions" in the exploration into music.

Music requires and relies on extramusical underpinnings, whenever the ideas of music theory are invoked, when aesthetic issues and criticism are asserted, when music involves text, narrative, movement or social function, and so forth. Moreover, music requires and relies on extramusical underpinnings, for the musical faculty has been posted as bi-directional and influenced continuously by the effects of its interfaces with the extramusical. Pre-compositional choices indicate such an interface, when the application of a conceptual structure or extramusical understanding influences the act of composition.

What is music? What is extramusic? The challenge to define music is not met by this model. Music, as an artifact of the musical faculty, can be of many kinds and instances. Music, as perception, is itself a personal and therefore limited definition. Music, as process, is the act of the mind, and the model, a propos of music, is directed toward a useful explanation of it. But, as with Bierce's humorous non-definition of art, a composer's theory of music need not define music, as it is in the act of composition that music is defined and redefined.

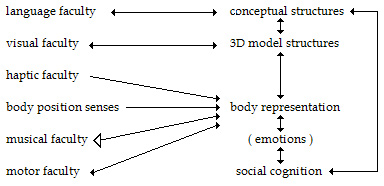

The model is asserted to variously define music, as circumstances require, by its very structure -- with hidden mechanisms of relatively simple properties. This monograph has repeatedly amended the Jackendoff model, identifying the musical faculty as both an input and output channel, akin to how Jackendoff identifies the language and visual faculties. [sec. 1.5, 1.7, 2.3, 3.4 and 3.7]

FIGURE 2.

A limited definition of music restricts itself within the hypothetical musical faculty; the broader definitions extend music into the interfaces of the musical faculty with other faculties and formats. Within the methodology of this monograph, it is only their utility and explanatory power which recommend varying definitions, as multiple probes with which to explore music.

Even as definitions restrict themselves for pointed explanatory purposes to the arena of the musical faculty alone, this monograph asserts that the musical faculty does not exist in isolation, as the diagram might suggest, but operates in tandem with other faculties and formats. Research suggests that "external aids or historically formed devices are essential elements in the establishment of functional connections between individual parts of the brain, and that, by their aid, areas of the brain which previously were independent become the components of a single functional system." [Luria, 1973, 30] Thus the musical faculty as a separate module is itself a useful fiction, in the Jackendoff model, or this monograph's amended version.

These seem to be the "human facts" which Sessions challenges a theory to respect. Music, in its many manifestations, emerges from the "hidden mechanisms with relatively simple properties" of the musical faculty (with all the neurological constraints of that faculty), and within the web of "functional connections between individual parts of the brain," reaching out and responding to the "external aids or historically formed devices" found in the world of music. Music is musical and extramusical. Music is both neurologically created and constrained, and socially and culturally shared and moderated, as conceived by an amended vision of the Jackendoff modular model of the mind. No single ideology which ignores these "fictional" and very "human" facts can make useful the breadth and extant range of all we call music, music theory and the many theories about music which comprise the web of discourse which centers itself on music.

Copyright © 1993 by Gary Bachlund

[This monograph served as the first of two volumes towards the PhD in Music, UCLA; the second volume is The Jerusalem Windows

, a seven movement suite for organ.]

REFERENCES AND OTHER RECOMMENDED READINGS

(alphabetically)

Adorno, Theodor (1992) Quasi una fantasia: Essays on Modern Music. (trans. by R. Livingstone) New York: Verso.

Albrecht, Timothy (1980) "Musical Rhetoric in J. S. Bach's Organ Toccata BMW 565," in The Organ Yearbook, XI.

Atkins, Robert (1990) Artspeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements and Buzzwords. New York: Abbeville Press.

Bach, Emmon (1964) An Introduction to Transformational Grammar. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Barthes, Roland (1968) Elements of Semiology. (trans. by A. Lavers and C. Smith) New York: Hill and Wang.

Barthes, Roland (1977) Music, Image, Text. (trans. by S. Heath) London: Fontana Press.

Barzun, Jacques (1982) Critical Questions: On Music and Letters, Culture and Biography. (ed. by B. Friedland) Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bernstein, Leonard (1976) The Unanswered Question, Six Talks at Harvard. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Blacking, John (1976) How Musical Is Man? London: Faber and Faber.

Blacking, John (1987) A Commonsense View of All Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bloch, Ernst (1933) "Man and Music," (trans. by W. Frank) in The Musical Quarterly, XIX, 4.

Bonds, Mark (1991) Wordless Rhetoric: Musical Form and the Metaphor of Oration. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Boretz, Benjamin and Cone, Edward (1972) Perspectives on Contemporary Music Theory. New York: W. W. Norton.

Boretz, Benjamin (1985) If I Am a Musical Thinker. Barrytown: Station Hill Press.

Cage, John (1962) John Cage Catalog. New York, C. F. Peters.

Chagall, Marc (1989) My Life (trans. by D. Williams) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam (1968) Language and the Mind. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Chomsky, Noam (1975) Reflections on Language. New York: Pantheon.

Chomsky, Noam (1988) Language and the Problem of Knowledge. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Churchland, Patricia (1986) Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind/Brain. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Churchland, Patricia and Sejinowski, Terrence (1992) The Computational Brain. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Churchland, Paul (1988) Matter and Consciousness: A Contemporary Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Churchland, Paul (1989) A Neurological Perspective: The Nature of Mind and the Structure of Science. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Copland, Aaron (1952) Music and Imagination. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Culler, Jonathan (1981) The Pursuit of Signs: Semiotics, Literature, Deconstruction. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Cummings, E. E. (1985) Is 5. New York: Liveright.

Davenport, Guy (1987) Every Force Evolves a Form. San Francisco: North Point.

Dennett, Daniel (1978) Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. Montgomery: Bradford Books.

Dennett, Daniel (1991) Explaining Consciousness. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Dewey, John (1959) Art as Experience. New York: Capricorn Books.

Dunlop, Charles and Fetzer, James (1993) Glossary of Cognitive Science. New York: Paragon House.

Epperson, Gordon (1967) The Musical Symbol. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

Fetzer, James (1990) Artificial Intelligence: Its Scope and Limits. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Fetzer, James (1991) Philosophy and Cognitive Science. New York: Paragon House.

Fodor, Jerry (1975) The Language of Thought. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Fodor, Jerry (1983) Modularity of Mind. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Fodor, Jerry and Pylyshyn, Z. (1988) "Connectionism and Cognitive Architecture: A Critical Analysis," Cognition, 28.

Forte, Allen (1978) The Harmonic Organization of the Rite of Spring. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Forte, Allen and Gilbert, Steven (1982) An Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis. New York: W. W. Norton.