Music and Texts of GARY BACHLUND

Vocal Music | Piano | Organ | Chamber Music | Orchestral | Articles and Commentary | Poems and Stories | Miscellany | FAQs

On Stereotypical Adjectives to Describe Music

I. THE ZEITGEIST

It has become popular to speak from various socio-political perspectives about music, such that the great majority of scholarship in musicological circles and criticism will treat "music by women" as a topic, with the obvious goal to advancing their works for the public. "Music by [ insert term ]" becomes a parsing method to group by cutting away using stereotypical assumptions, study in isolation, and then place in opposition to other groups, usually to some stated socio-political purpose.

Similarly, one reads from time to time about either "no music by dead white men" [ 1 ] or "white privilege" in the critique of classical music in general and composers in particular. As one example among many, here is a quote by festival director Brett Sheehy:

"So, rather than bringing in grand orchestras and presenting the dead-white-male canon, I wanted classical music concerts to have a primary focus on living composers and contemporary work. I did it because it would alienate some people." Quote by Brett Sheehy in "Classical music is a 'tyrannical' term, says Melbourne Festival director," by Melissa Lesnie, Limelight Magazine, 13 September 2011

These and other related social constructs disturb because

they are intended to disturb, but one may place all this in the fine perspective of Igor Stravinsky who noted in one of his Harvard lectures that many speak about all the socio-political sides of our world of music as well as story lines in libretti, personalities and opinions and more, because to speak about the music itself is most difficult. One may conclude that these other streams of thought then are by comparison "easier." While this may well be true, I contend that assigning stereotypical adjectives to music and then extrapolating from such adjectives are fraught with problems, inherent in language itself and the function of adjectives bluntly applied. One must then consider both methodology and meaning.

Given notions of culture, locale and ethnicity, language, race, gender and even now sexual orientation as one finds them romping through journalism, public discourse and musicological circles, one finds assertions that there is -- as a few examples among many -- German music, black music, Christian music, urban music, folk music, and certainly women's music. I would argue that all this smacks of old fashioned salesmanship and simple advocacy for one class of products over another without specific regard to individual merit and used as some sort of method of socio-political redress at injustices real and imagined, and not a high-minded attempt to level the artistic and aesthetic playing field for the sake of equality for all, whether they be representatives of cultures, linguistic groups, racial stereotypes, genders and sexual preferences. Let us examine cursorily a general subject, story lines, history and the music which has come to be through such a seminal stimulation of narratives, texts and music.

II. THE STORYTELLER - SHÉHÉRAZADE

In addition to Maurice Ravel's orchestral overture bearing the same name, his other Shéhérazade is a song cycle from 1914 for soprano or tenor solo and orchestra, after three poems in French by Tristan Klingsor, the pseudonym of Arthur Justin Léon Leclère (1874-1966). The poet writes, beginning with the French name for "Asia." "Je voudrais voir Damas et les villes de Perse /Avec les minarets légers dans l'air." Damascus, the cities of Persia and its minarets. Later, "Je voudrais voir la Perse, et l'Inde, et puis la Chine...." Persia, India, and then China. The voice makes its opening plea to Klingsor's text over a hushed tremolo of muted high strings and introduced by the plaintive solo oboe. Asia! Asia!

Is this song cycle then French? By language and national origin of the poet as well as composer, the simple answer is clearly yes. By subject matter, the answer is a resounding no. By genealogy, the answer must also be no, for earlier works on which Ravel's cycle is based are certainly not rooted in French culture, language or history. If one would argue that this song cycle is "French" without relying on the stereotypes of national origin and language as deciding factors, one then need show what musical elements and where they appear in the score are French and cannot be confused with other adjectives' describing national origin and language. Is the opening pizzicato in the lower strings French? Is the tremolo in the divisi first violins French? Is the limpid solo oboe's melodic arch French? If such questions cannot be answered yes, then musical elements are not the deciding factor in modifying the noun, music, with an adjective.

If the argument were to be advanced that because Ravel was French, then his music is also French, one need then look to other composers who have lived, worked in or even immigrated to another nation in their lives, in order to make consistent this labeling practice.

Ravel's overture from 1898 is without text, and as such reference to language as supportive of the descriptive adjective "French" cannot be made as easily as with the song cycle. And yet Ravel was moved enough by the narrative named after a character in its broad images and Asian references to base two works on the same extra-musical themes. The example below is drawn from the four-hands arrangement:

The tales are centuries old and have been interpreted through the linguistic and pictorial peculiarities of many languages and cultures. As William Wordsworth says in his The Prelude (1850) which predates both Ravel works:

I had a precious treasure at that time,

A little yellow canvass-covered book,

A slender abstract of the Arabian Tales;....One small reference to the storyteller of legend is found without text in Robert Schuman's piano collection, in this German composer's "Scheherazade" from Album für die Jugend, Op.68, no. 32, composed in 1848. Only decades earlier, we see that Sheherazade was German by any descriptive practice of employing adjectives of national origin. What musical elements in the example below are in fact German, aside from the score markings?

Sheherazade is also an orchestral suite composed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1889, based on tales from the famed "One Thousand and One Nights," an English-language collection of 1706 which is itself stems from a collection of folk tales stemming back to the Islamic Golden Age (from the 700's to the 1200's) with likely earlier antecedents drawn from Sanskrit tales far removed from the various cultures of Islam. Indeed in this "modern" day, some radical Muslim theologians would happily quash the folk tales, the music associated with them, and even the cultural artifacts such as visual art by which one may trace the evolution of the story and musical repertoire extant today. This powerful work for orchestra is represented below in its piano reduction, to sample the first musical gestures so unlike those of Robert Schumann, and Maurice Ravel to the texts of Tristan Klingsor. A symphonic poem, only the title and therefore pictorial and dramaturgical references tie this music to the ancient tales.

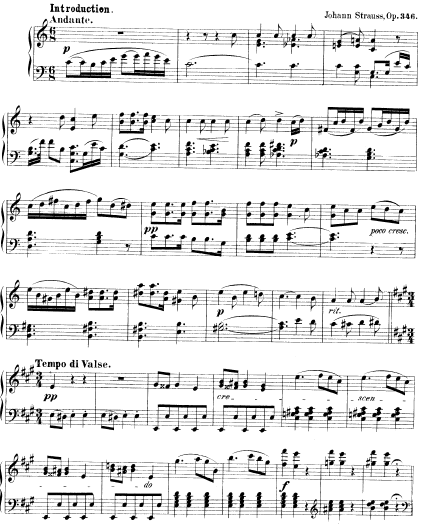

In addition to Ravel, Schumann and Rimsky-Korsakov, the tales have been a foundation on which many other art works have been constructed, by such as operas by Carl Maria von Weber with a libretto in German, and François-Adrien Boieldieu with a libretto in French, Luigi Cherubini's Ali Baba, ou Les quarante voleurs, Peter Cornelius with his own German libretto, Carl Nielsen, and even Richard Wagner with his unfinished Die glückliche Bärenfamilie. Of course, beloved waltzes include opus 346 by Johann Strauss II based on the tales, his Tausend und eine Nacht.

So as to Ravel's Shéhérazade -- which we heard in concert conducted by the admirable Michael Gielen and the Staatskappelle in the last month at Berlin's Philharmonie -- the question may be formally addressed. Is it French music? If so, specifically why in terms of musical elements as distinct and demonstrable? Or given its exotic colorations, something else? Is it Arabian music? Is it French music in parody of or in appreciation of Arabic music? If one may affirm that it is most accurately called French, then comes the similar question about Bizet's Carmen.

But before considering another narrative, another text and another opera, let us consider the following questions: 1) What are the musical features of "French" music which descriptively set it aside from German, Austrian or Russian music, or music of yet other lands? Are there specific chords, chord forms or structures which are so characteristically French that they cannot be German? Or English or Italian? Paring away the issue of national identity of a composer and the language of a sung text, I assert that the adjective "French" says little to distinguish Ravel's Shéhérazade from Rimsky-Korsakov's Sheherazade or Schumann's lovely little piano work and Strauss' waltz. In like manner, I assert that "Russian" and "German" do not adequately explain these other works of the same title and supposed subject matter. It seems, with the admonition from Stravinsky resonant in thought, that the purely musical features of these "Arabian Nights" works of music cannot be characterized by adjectives of language and national identity. And yet they are, for the reason Stravinsky has told us. It is easy to do, if generally of little musical substance.

III. OTHER STORYTELLERS

Based on a French novel by Prosper Mérimée about characters enacting their tragic fate in Sevilla, Spain, is George Bizet's Carmen French music? Given that the famed Habanera was adapted from the habanera "El Arreglito," originally composed by the Spanish composer, Sebastián Yradier, and acknowledged as such by Bizet, is this aria representative of Spanish music or of French, or of both? When thinking of the text alone as a criteria by which to employ the adjective, French, one can point to Mérimée and the co-librettists Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy as definition enough. And yet the story is of Spain and Spanish characters with regional differences. And when such an opera is sung in a translation into another language as I and many others have done in careers now past as to the present, does it become English? Or German when sung in yet another translation, as previously decades have shown? Among professional singers I have known, one well-reputed mezzo soprano had sung Carmen in two French versions, as well as three English languages translations of lesser merit. Is Carmen then French and Spanish and, when in translation, English as well? And specifically as to the beloved habanera, is Yradier's Spanish while Bizet's version is French? If so, having common musical elements from the key to the dotted, arppeggiated bass line to the melodic line slipping by half steps, none of these wholly musical elements may be said to be either, or all must be both Spanish and French.

The pictures of an adjective -- French, as in the examples above -- of either national origin or language paint are of simplistic notions without examining the underlying realities and foundations on which works are built. If one drops language as an identifier, then what remains? A composer's national origin alone? And yet Yradier was indeed as Spanish as Bizet was French. And neither could be said to be German, but....

Surely Wagner's German-language Tristan und Isolde has its history, based on an earlier retelling by Gottfried von Straßburg from the 13th century, and yet the tale in very early German tells the courtly tale of a French hero in service to an English king and love affair with an Irish princess. But the Norman poet Béroul wrote an early French of Tristan et Iseult, and yet a predecessor is Thomas of Britain. As to the story, is it Irish? English? French? German? When one examines the story lines and texts on which musical works are often based, assigning a national origin can become mired in complexity, a genealogy mixed between languages and sensibilities over centuries. Is the tale of Tristan German? If sung in a libretto and music by Richard Wagner, this tale which occurs between Ireland and Cornwall, and ends in France is often deemed to be German. I find this ever more odd, for then language or national origin of the composer is the only criteria by which the adjective is applied. Moreover, a number of my German colleagues have often made the distinction between Deutsch and what they say is "Wagner Deutsch." for the grammatical idiosyncrasies in his libretti. Might we then make a distinction between other "German" music and Wagnerian music? And if we do, what assistance is that to us? Having sung the role in a number of different productions, my own views are most personal and hands-on. For this reason among several, I bristle at too light an application of adjectives. The opera is indeed most often sung in German, but the characters and their interactions are most human, an adjective far broader and more profound than "German."

For the most part, the rationale is always one of language and national origin, but there are absent defining musical examples -- chord structures, melodic constructions, harmonic progressions and successions, orchestration colorations, and the like. Such true musical examples are rarely used to make assertions as the adjectives of national origin and language so easily seem to do. The famed Tristan chord is nothing but a diminished triad with a minor seventh in root position. This chord is found throughout the 19th century in many other European composers' works, and used in a variety of harmonic progressions. I argue that the Tristan chord is not that it is a chord at all, but rather a musical gesture of melodic specifics and a specific harmonic resolution given specific voice leading by distinctive orchestra colors which make evident what a single chord does not.

Then the problem becomes ever more a conundrum as such adjectives of national origin dilute under scrutiny. What of the narratives themselves? The early Germanic tales of Faust filter through Christopher Marlowe's Faustus, to Goethe's Faust and lately into Mann's Doktor Faustus, and yet the composer, Charles Gounod, set Faust to a libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré in French. Then is Faust German, English or French? Berlioz' La damnation de Faust is filtered through a reinterpretation of Goethe, so is it wholly French? The living French composer, Pascal Dusapin, has yet a new Faustus, clustering along with Ferruccio Busoni's Doktor Faust of a century earlier into a collection of operas on the same story. But Busoni was of Italian origin while he fashioned his own libretto is in German. Is Faust then French? Italian? German? Franco-German? European?

As we have been using a few adjectives to describe national origin and language, there are other sorts of adjectives which have come into play, and the Zeitgeist of our time asks for even more descriptive adjectives generating their own issues and conundrums. All of the above composers, poets, writers and librettists can be described as white, male, European and -- yes -- dead. But more adjectives lurk.

IV. ADJECTIVES LURK

Given that the marvelous bass role in Gounod's opera is Mephistopheles and as Marguerite is carried away to heaven, is the opera in fact Christian? Catholic? French Catholic? French Catholic, and white per the terms of the racial argument, and male per the terms of the feminist gender-aware stance. What have we then done, except made a range of political arguments telling nothing about the music itself, or even addressing the subtleties of the story's treatment by a librettist?

The Catholic church is a feature in the libretti of many operas, so might one suggest that these operas are in part capably described by the adjective, Catholic? And yet the Russian Orthodox Church is featured in some operas as well? Another denomination of Christian opera? And yet Wagner's Parsifal rests in part on a stream of narrative from Christianity and another from the dark art of magic. How then would indentifying such musical works by religious adjectives suffice? Pietro Mascagni, through his librettists Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti and Guido Menasci, places characters outside church at Eastertide. Is Cavalleria Rusticana in part Italian Catholic? Might the five act opera, La Juive, by Fromental Halévy with an original French libretto by Eugène Scribe then be said to be Jewish as well as French?

If Ravel's Shéhérazade is French and Rimsky-Korsakov's Sheherazade is Russian, while the stories are Persian, or perhaps even better said from the original Sanskrit as some scholars say, then we have a work of art with many members in its family history. Just as my family immigrated from Sweden to the United States, while I live in and write this as a resident of Berlin, Germany, the question of origin and assigning adjectives to describe musical works becomes quite convoluted. A Gordian knot tightens which tells ever less about the music itself, its melodic contours and harmonic palette, its forms and development stratagems, its instrumental and vocal colors, but exposes well our shifting and temporary Zeitgeist about politics too easily read into art.

In the moment, adjectives and stereotypes run wild, courtesy of the influence of socio-political thinking attempting to hold sway over our elusive and wondrous domain of music, musical thinking and musical works. I call much of this folly, while much of the musical world calls such prose about music musicological inquiry. But in this I rely on Stravinsky's observation that people talk about the periphery of music, because to speak about the music itself is both difficult and rarely admits the validity of such stereotypes as descriptions.

V. RACIAL DESCRIPTIONS

William Grant Still (1895-1978) has been called "the Dean" of African-American composers. His Troubled Island is usually said to be "an American opera" -- there's adjective of national origin appearing so blithely -- in three acts with a libretto begun by poet Langston Hughes (1902–1967) and completed by Verna Arvey (1910–1987). Arvey married the composer following their collaboration, and so the collaboration is between a black composer, and first black librettist and then a white woman librettist. Set in Haiti in 1791, the tale is about a French-black culture, which one reference states was "composed by Americans of black racial stock," but rather than be in Haitian French the libretto comes from the Harlem Renaissance period and is in English. Is this opera American or Haitian? Is the opera black or white? Or should the earlier adjectives from anthropology, Negro and Caucasian, be used? Is the opera Christian in the sense that its creators were a part of the Western Judeo-Christian religious traditions? But with a female co-librettist, can the opera be said to be by a male? Verna Arvey Still was a versatile creative artist in her own right, and had a dual career as concert pianist and journalist, but if one is to speak of Still on the basis of his race and ethnicity, then one might also color the picture with hers. She was of Russian-Jewish background, and this considerably muddies the ease of applying adjectives to describe musical works. If we dismiss her as female, white or only the author of texts, then this leaves music alone in which we must rummage about to find markers which determine the value of adjectives such as "black" or "American."

A half a generation earlier, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) was an English composer born in London who achieved such success that he was once called the "African Mahler". Was he English? African? A kin to Germans, by the complimentary comparison to Gustav Mahler? Are his works both black and English? Does this define in some way a difference between what is means to be 1) male, black and English as opposed to Still who was 2) male, black and American. If so, one must confront other interests of Coleridge-Taylor, for he wrote A tale of old Japan, his Opus 76 (1911) and more confusing still his Hiawatha Ballet in five scenes, Op.82 (1920). Is one work Native American while another is Japanese, and yet also African, or are all these works English and black and Japanese and Native American? The texts he chose for his song settings range from Caucasian Europeans and Americans like Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barret Browning, Walt Whitman, William Wordsworth, Christina Georgina Rossetti, Lord Byron, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, to black American Paul Laurence Dunbar. Are song settings to "white" poets by a black composer black or white? Conversely are songs settings to black poets by white composers white or black? Such complexities do not come from the music itself, for music can only be said to have musical complexities, but rather from fumbling use of adjectives to paint a musical work as "x" as opposed to "y." Or is what follows with a libretto by a white Englishman on the subject of Japan authentically black music? Or English music? Or the work of an "African Mahler?"

William Christopher Handy (1873-1958) was a blues composer and musician, and among the descriptives used, he is widely said to have been as the "Father of the Blues." Yet a contemporary musician of W. C. Handy is far more obscure to us today. Hart A. Wand (1887-1960) was an American early fiddler and bandleader from Oklahoma City, of German extraction for his family came from the area around Frankfurt. In the musical world he is chiefly noted for publishing the "Dallas Blues" in March 1912 and copyrighted in September of the same year. "Dallas Blues" was the first ever published twelve-bar blues song, and so the question lingers. Given that "blues" is an adjective of changing criteria based on each era in which it is applied, is "blues" in fact only black? Little is known about Wand, while W. C. Handy has received much attention. Wand's father John was a German immigrant to the United States, moving about from Kansas to Oklahoma to Chicago to New Orleans, as documented in Samuel Charters' The Country Blues (1959). Is this first published blues song white? European? German? American? What is there about the blues in all its various forms that so easily asserts the adjective "black" while musicians of other racial groups continue to also compose blues across a century? If a twelve bar blues is blues, can a white bandleader and fiddler with a German family background have written an "authentic" blues, or does racial stereotyping wash away this historical fact?

Given that black and its variant African-American have become almost synonymous with blues, while other racial groups employing the form and styles are dismissed, one might consider another and perhaps less well known musician, George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower (1778-1860). He is said to have been an "Afro-Polish-born virtuoso violinist, who lived in England for much of his life." But we also learn that Bridgetower was born in Biala in Galicia, a region of northwestern Spain, and that he was baptized with the given name of Hieronimo Hyppolito de Augusto (1778). So here is an interesting problem of adjectives, as relate to issues of national origin, language and race. The following adjective might apply: black or of mixed race depending on the opinion of a scholar today, African in some degree, but Spanish by location of his birth, but English by his residence, and yet with that Polish side which tells something of his genealogy but nothing of his music. As a contemporary of Joseph Haydn, Beethoven's Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major (Op.47) was originally dedicated to him, before an argument brought a rededication to Kreutzer. This musician of historical note is not well served by parsing away some of his story to highlight another, and yet his opera omnia is found in the 1990 edition of Black Music Research Journal. Is his music then black? African? Polish? English? Spanish? The adjectives contend with one another as seemingly mutually exclusive, for the same reasons as summarized above with the works based on the tales of Sheherazade.

While black American composer Eubie Blake and his lyricist and librettist Nobile Sissle wrote "black" Broadway musicals, these pale in public awareness to the music and lyrics of George and Ira Gershwin in their seminal Porgy and Bess, to a 1925 book adapted for the stage by the author, DuBose Heyward. Heyward additionally wrote some of the memorable song lyrics along with Ira Gershwin. Is Porgy and Bess a black work? A white work?The Gershwin brothers were of Ukrainian Jewish lineage, born in Brooklyn, New York. Is Porgy and Bess European? Jewish? Once the question of origins of composers, librettists and lyricists rises, such adjectives as tell something of their backgrounds also confuse issues of the music itself. Given the prevalence of such adjectives, one might ask a comparative question: Is Coleridge-Taylor's A tale of old Japan more black than the Gershwins' Porgy and Bess? Such a question begins to demonstrate the folly of descriptive adjectives' ostensible power and the wisdom of Stravinsky's observation that music is a most difficult subject about which to speak and write with such non-musical terms as are these various adjectives and many like them, while lingering on the musicological periphery seems so pertinent and informative when adhering to the prevailing socio-political Zeitgeist.

We are left with profound adjective-tainted questions. Can three white American males, two of them Jewish, compose a distinctive and well-beloved "black" opera? Can a black English male compose a Japanese opera to English-language texts? For that matter, can an Italian composer create a Japanese opera with an Italian text? Can a black American compose an opera in English about the Haitian French? But adjectives abound.

VI. GENDER DESCRIPTIONS

Sally MacArthur (Feminist Aesthetics in Music, 2002) asks: "Is there such a thing as women's music? Do women write and listen to music differently than men do?" She argues that "20th-century music is inextricably bound to notions of gender that transcend aesthetics." I would argue that it is no longer a question of either aesthetics nor of music itself when one raises the specter of "notions of gender," for we have seen above that notions of national origin, language, religion and race are not as powerful descriptors as those who happily employ such adjectives would have us conclude. MacArthur chooses her words precisely, and among her descriptive adjectives to pursue her argument is "undervalued" as regards women composers. But gender has become a broad and heavily broken notion as description, for the feminist approach would seek to examine women, whether heterosexual or lesbian, but fails then to rally the same argument for homosexual, bisexual and transgendered composers, librettists and lyricists.

Let us consider Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979), an extraordinarily influential teacher as well as composer, among whose students are found Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Ned Rorem, Philip Glass, Virgil Thompson and Marc Blitzstein. George Gershwin sought her out, and Igor Stravinsky was a friend. In looking through the list, one notes a peculiar fact when viewed through the lenses of "women's music." The most significant of her students were men, not women. Is Boulanger as composer "undervalued" when compared to -- say -- Aaron Copland? The adjective is powerful, accusatory and as with many of the adjectives above employed for socio-political ends more than musical. Is Boulanger's music French? Certainly her choice of texts she would set was consistently French. Female? Not all her texts fulfill the goal of that adjective. And yet her students, mostly males, did not compose French music but rather sought out what she urged them so to do, i.e., speak in their own distinctive musical voices. That has little to do with adjectives of gender, and yet such as MacArthur's questions are the subject of much scholarly exercise in today's academic circles.

History does inform us without controversy that women accounted but for the small percentage of the population of composers in any given era. We may look back and see women as composers for centuries. One finds Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) though Bingen then was not the nation of today's Germany, Beatrice de Romans of circa 13th Century France, or Birgitta of Sweden (c1303-c1373) as examples of this. Were they the original feminists, one might ask within the arena of modern musicology? But what would an answer to this purely socio-political question yield in making their music more highly valued or more often performed. Might one postulate that if "no music by dead white men" has some musical value in the modern ear, might "no music of dead white women" not be an equivalence? If the Western canon of music can be characterized through the feminists' view as an example of "male hegemony" or "white privilege," then what should one do with Ravel's Shéhérazade with which this commentary began? Supplant it in favor of music composed by women? Suppress it as an offence against the socio-political correctness of today's Zeitgeist?

One finds modern feminist musicology examining more closely Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677) who was also called Barbara Valle. She was an Italian Baroque singer and composer, and therefore of logical interest to the feminist perspective. One finds a number of her scores now available in our modern time on line, as well as a list of her works documented at Emily Ezust's fine site, The Lied, Art Song, and Choral Texts Archive. Strozzi's Italian Baroque works are, of course, characterized as Italian. Indeed, like Boulanger, the many vocal works are of one language. but the texts are in part her own, and many are by her adoptive father, Guilo, who is also said to have possibly been her biological father. What then shall one say of Strozzi's works? Are those to her own texts more feminine than those which set her father's texts, which then must be declared male in some part? What portion of the music but not the texts is an example of feminine composing?

Where in the melodic contour or harmonic progressions is there evidence of a woman's compositional hand as distinct from a man's hand? MacArthur states that "20th-century music is inextricably bound to notions of gender that transcend aesthetics," so should one conclude that Strozzi, a compositional student of Francesco Cavalli, was writing male music? And aside from the text being in Italian, where are the proofs for national origin, given some salient historical facts, among them that the adjective Italian means something quite different today for a relatively new, post-war European government than it did when Venice was itself a republic which survived about a thousand years.

One cannot argue that the 12/8 meter is any more feminine than masculine, and any more Italian than German or or French or American. One cannot say that the tonality speaks in a feminine voice any more than in a masculine voice excepting for the historical fact that Strozzi herself sung her own music. Additionally we know that Strozzi's works include religious texts, and so one may ask is this work feminine, Italian and Catholic? If the answer is yes to any of these problems posed by such adjectives, one should be prepared to show what in the music-as-music gives evidence to this. But the modern and prevailing Zeitgeist dismisses calls to examine the music itself for evidence.

Susan McClary (b. 1946) is an American musicologist and part of what is called the "New Musicology." Her text, Feminine Endings (1991), was among the required reading for some of my course work, and in it she asserts that the term "feminine ending" be reinterpreted, and that, as one example, the sonata form is evidence of sexism, misogyny and imperialism. Of course another work, Conventional Wisdom (2000) would identify my view as a "conceit" used to hide social and political imperatives which supposedly uphold the Western canon in some unfair and therefore sexist manner. We may conclude then that it becomes more important to supplant Ravel's Shéhérazade -- the example which is first presented -- in order to redress injustice based on issues of gender. Ravel becomes a member of the "dead white men" club, while Strozzi does not become a member of the "dead white women" club, based on similar socio-political constructs. Susan McClary is white, as best I understand her racial background. Should she too be supplanted in favor of another racial grouping? Arguments often cut in more than one direction.

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (b. 1939) is a prolific and honored American composer. She is also white, English speaking and of course a woman. Much of her opera omnia to date in instrumental, but one 14 minute long song cycle, Einsame Nacht (1971), sets texts in German of the poet Herman Hesse and is composed for a baritone to sing. Is this work then wholly feminine, especially given the assertions of feminist musicologists? Is the song cycle American or German? Is it Caucasian or white music? I do not intend such questions as offence to Zwilich, but rather to hopefully parse away the socio-political stances in favor of seeing her work as music in of itself, of value as music rather than as representative of a political, racial or gender stance. The questions posed by adjectives of national origin, gender and language do not assist in approaching the music, and it is music and musical meaning with which a composer invests in notation and sounds when performed. Personally I do not find that she needs any assistance from the adjectives, for she may be seen as a composer far more than a politician or set of chromosomes or representative of a class of societal victims. One among many, but a composer nonetheless.

Thea Musgrave's publicity identifies herself as a Scottish-American composer (b. 1928). Her large body of fine work ranges from instrumental to vocal and the dramatic. Herein and unlike Ravel and Boulanger both as uniquely French is a hyphenated adjective to tell of national origin. As one sees, she too is racially Caucasian. While generally it is not of value to continue to identify gender, race, national origin and language in conversations about an individual composer's work, we become immersed in such adjectives courtesy of the Zeitgeist. We may seen Musgrave's Scottish side in a song cycle, Five Songs For Spring (2011) to text by Robert Burns and composed for baritone. Again with the thought of adjectives, how American might such Scottish texts be? How feminine might be a setting of a man's poetry? What does Musgrave's choice of a baritone say about gender in music? I would contend it says little, even to the point of being counterproductive. But her interest is indeed demonstrably Scottish at times, as one see in her opera, The Abbot of Drimock (1951), with a libretto written by Maurice Lindsay, based on one of J. M. Wilson's Tales of the Borders, Scottish Border Anecdotes from the 1880s. Shall we say this opera is Scottish? Like Verdi's Macbeth? Should this work supplant Verdi's for the socio-political goal of redressing the injustice of white privilege or male hegemony in the compositional arts? While such questions trip over into the ludicrous, they are brought into discussion by the underlying assumptions of stereotypical adjectives used to further distinctly non-musical goals.

VII. SEXUAL ORIENTATION ADJECTIVES

The length and breadth of musicological inquiry spun into complexity by adjectives and socio-political fundamentals which have little to do with music itself and especially with music's values, one comes to the latest gambit in adjectives applied. There is, we are told, another "New Musicology" like unto that asserted by McClary and this is "Queer Musicology." UCLA's Mitchell Morris examines such issues as gay men in opera, like unto the feminine endings arguments as above. But what of gay composers? The above-mentioned McClary addressed in a 1997 article, "The Impromptu that trod on a loaf," issues about Schubert's Opus 90, no.2, so is a feminist musicologist also capable of functioning as a gay musicologist, asks the standard operating procedure of applying adjectives so freely? But to the subject of homosexual composers:

Today's Zeitgeist is busy identifying some composers as gay -- Benjamin Britten, John Cage, Samuel Barber, Francis Poulenc, Hans Werner Henze, Karol Szymanowski, Ned Rorem -- with musicological disputes about historical figures such as champion bisexual Jean-Baptiste Lully, Camille Saint-Saens, Franz Schubert, and of course everyone's favorite, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. And so, as the adjectives spin out their supposed power, one must ask of the music but not the individual, what makes a piece of music homosexual in its musical make-up? The intellectual dodges are readily erected here, as one might allege MacArthur's "20th-century music is inextricably bound to notions of gender that transcend aesthetics." So gender and in this case sexual preferences transcend -- but transcend what exactly? One might examine yet another score excerpt and require of its musical content, what makes this music evidence of sexual orientation per se. Is it found in the melodic or harmonic content, the arch of musical gestures, or even the subject matter. But when a text is absent, when then? Does Lully's documented "libertine" proclivity inform us of anything musical at all? If so, what?

McClary's tactic is to declare such questions a "conceit," while the opposite might be well and fully alleged. Is Lully undervalued, as we employ an adjective dear to the socio-political stance of MacArthur? To paraphrase her question about feminist music, is there indeed bisexual, gay, lesbian or transgender music? If so, what are its musical components? Is Lully also evidencing white musicality rather than that of another racial grouping? Is he demonstrating further what is means to be French, in some way that might enhance an understanding of Ravel's Shéhérazade of 1914 as French in some similar but non-linguistic manner? The competition between stances as use of adjectives shows becomes a jolly folly. Lully and Ravel are both now "dead white men." What does this say about their music? Are they all evidence of "white privilege?" Do Zwilich and Musgrave have their reputations in part because of "white privilege?" Or Boulanger? Are Ravel and Schumann both evidence of something European, given the fact that Shéhérazade is of Persian origin in its subject. Is Lully's Alceste as a libretto by Philippe Quinault, after Euripides’ Alcestis proof of white male European culture? It is a tragedy about a queen of Thessaly, abducted and with a narrative populated with Greek gods and men and women. What is bisexual about this in musical terms? What is white about this when looking into the score? What is in fact masculine about this in terms of structures, textures, melodies and harmonies and instrumentation? But the adjectives rise up as they are used, limp in explication yet powerful in socio-political and emotional terms, which the Zeitgeist of our times suggests is somehow of power to explain something musical.

VIII. A PERSONAL APPLICATION OF ADJECTIVES YIELDS LITTLE

Having performed Britten and Cage, Rorem and Poulenc, Copland and Bernstein, all bisexual or exclusively homosexual, what does this say about me as a performer in the socio-political terms as erected in a monument to a "new" musicology itself? I have met several of them during my career, and consider each as an honor in my life. But I also contend this tells little, if anything at all. I further contend that it is in the quality of the music which cannot be informed by such adjectives as describe per all the above that my enjoyment of the work as performer as well as consumer lies.

Some of my work as composer lies across ten different languages, the largest body in English and the second largest auf Deutsch. Does this evidence my music to be American? White? Heterosexual? Alas, I have set gladly texts by non-Americans, by non-whites, and by non-heterosexuals. I suggest this tells nothing -- not little, but nothing -- about my music. My deep appreciation for Paul Laurence Dunbar is evidenced by over fifty song settings in both standard English and his delightful use of dialect. Is such music then only white, or part white and part black? Do such questions say anything about the music itself? My answer is no. What does it say about my racial background? Nothing. In the same fashion I have been drawn to some works stemming from the Harlem Renaissance, but not for their being in any way identifiable as racial. Rather because the best work of that time transcended such meager, fumbling descriptions as "black." Or white. Or gay or straight. Or male or female.

My love of Joachim Ringelnatz is shown with over sixty song settings in German. Is this part of my music German? Are my German settings American? Or my settings of Yiddish texts? Or French? My admiration for the poetry of Else Lasker-Schüler is demonstrated by a number of song settings also. Is this particular output German? Jewish? Feminine? My settings of some texts by Erich Kurt Mühsam cannot identify me as socialist, though he was both one per his own words as an early 20th century socialist and also murder victim of the National Socialists of that time in Germany. My settings of texts by Sara Teasdale and Emily Dickinson do not evidence a feminist socio-political stance on my part any more than they contradict some other view, and my settings of texts by Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman demonstrate no leaning towards homosexuality not resentment of its place in society. My choice to set some texts from the poets of the Harlem Renaissance makes no statement about issues of race per se, but rather was a matter of sheer delight and appreciation for texts from poets like James Weldon Johnson. Such conclusions are easily yet falsely made by applying adjectives as if they had more explanatory power than they actually possess.

Moreover among the professors with whom I studied at UCLA was my friend, the fine composer, teacher and publisher Roger Bourland. Shall one assert that I learned "straight" composing from a gay man? Or that I learned in part to compose with in a "gay" style for having studied with him? Can any such associations carry explanatory weight to the music that I compose as one of his students? To the music which he composes and as a student of his teachers? Among his collaborators and among those texts which he has chosen are straight and gay alike, men and women too as one sees in his two books of Emily Dickinson Madrigals, so which tell much and which tell little? Of his many instrumental works, in which do specific musical gesture prove his sexual orientation? Which do not? I know well of his personal life and do not find his music "gay." Has he treated gay issues through the selection of texts? Of course. But stripping away the texts, where in the music is such other evidence to be found? Does he represent white music, American music and does his being a Caucasian American add to the suppression of music by women composers? It was my honor as an alum to support his receiving a distinguished teaching award; it was not a "gay" distinguished teaching award. Nor straight. Nor white nor male. The adjective, "fine," works very well to define Roger as teacher. Other less effective adjectives would only confuse, obfuscate or even interfere.

Ah, those adjectives stating stereotypes explain so little when they bump into each other's socio-political domains and advocacy for some group over another. I refute the use of adjectives to adequately describe my music as masculine, as white, as American, as of Swedish lineage, as liberal Jewish and free thinker, as individualist, as a resident of Germany, or as a traveler of the world. In fact, it is the socio-political "conceit" -- in McClary's terminology -- of those who would so ardently apply adjectives of national origin, language, race, gender and sexual orientation which interferes with the music of it all, and precisely for the reason as Stravinsky observed.

The fine song composer Ned Rorem composed in several languages, and lived for some time in France. Which adjective of national origin describes his music? Britten composed while in the United States, so which of national origin is his work? Examples which break the "conceit" abound, while the socio-political Zeitgeist will mount up its current defenses against such basic truths until such time as some next and other Zeitgeist takes hold, washing away today's.

What is certain from a marketplace perspective is that all of so-called classical music is a very small part of the world of music, and that the Western canon is being attacked for some rather obvious socio-political reasons. But this attack is a now century-old gambit becoming a parody of itself, from the time of the Frankfurt School forward into cultural Marxism and the battering ram of political correctness attempting to control individualism with the collective's cudgel, be it political or artistic. For this I wrote a poem as my parody of this time in history and then set it to music: Musicological Marx.

Is my text political? Indeed, but not for advocating any political party in any one nation, but rather to poke serious fun at the socio-political and academic games of today, given that so many composers of different races, genders and sexual preferences all would love nothing more than to be more highly rated in that musical canon about which so many seem to despair as too white, or too European, or too dominated by men, or too supportive of something which today's Zeitgeist pretends to attack all the while rather seeking to nudge aside enough for the newest and latest to become part of the canon. Is the music political? I'd laugh, were one to answer that it is. while the song by virtue of its text is, the music is -- well -- music with features like a 6/8 meter, a key center and progressions, repetitions, and musical quotes from other sources, and much more including some melodies borrowed from other composers. But such are musical features. The text? Mostly English, with some French and some German, composed in Berlin.

Musicological Marxism, parlez-vous?

Western culture's imperialism? Oui! Beaucoup!

Dead white guys, they all wrote lies,

That's the truth, and it implies...

Musicological Marxism!

Anglo-American Marxism: qui êtes-vous?

Frankfurt had the finest school? Ja! It's true!

"Das Kapital's" a pretty tune;

Radical thinkers gush and swoon.

Musicological Marx! Their hymn!

Postmodern critical theory is parlayed too? Parlez-vous?

Culture's revision is made for you. Oui! Beaucoup!

Throw the past out, for its sins!

All's passé just like zeppelins!

Musicological Marx! That's him!

"Wer hat recht?" is incorrect. Parlez-vous?

"Was ist schön?" means disrespect! Ach! So true!

Beauty is no judge of things,

The coming revolution sings!

Musicological Marxism!

Marx is dead, and he was white! Oh, so true!

Marx was male and, as such, right. No? Says who?

If dead, white guys have written lies,

Why praise this one to the skies?

Feminist, social and queerly emotional

Marks the larks of Marxism!

Is music phallic, or just Gallic?

Is music gendered or have race?

Colonial music plays at conquest,

Imperious music's a disgrace.

Thumb your nose at loveliness? Mais, pourquoi?

"Kult der Häßlichkeit" is such la-di-dah!

Cheeky is as cheeky does,

In the blur of a blinding buzz -

Dick meant Richard -- Wagner or Strauß,

Now it's phallologocentrism's cross-dressing's blouse.

Musicological Marxism, parlez-vous?

Western culture's imperialism? Oui! Beaucoup!

Straight white guys (like Marx?) told lies,

That's the truth, and it implies...more

Musicological Marxism!

But what part of the musical structure is representative of an anti-Marxist stance? None. Or being white -- like Marx? None. Or American, as opposed to English, remembering that Marx worked and died in England and is buried there in Highgate? Not at all. Or does the music participate in a French or German culture, per these languages appearing as part of the parody such that it cannot be also termed American? What silly questions one can ask: What sexual orientation is to be found in the musical gestures, harmony, form? Or do such adjective-laced questions have any bearing at all on the music?

IX. THE COMPETITION FOR ATTENTION IS THE GAME AND GAMBIT OF THIS ZEITGEIST

Let us go back to Mozart, whose operas have libretti in German as well as Italian, while he worked also in the area now known as the Czech Republic and in Austria. Which is he? German? Prussian? Austrian? Salzburg claims him. They are not alone in this. And given the many religious settings he composed, is his work Catholic or -- based on Die Zauberflöte -- Masonic? Can his Eine kleine Nacthmusik be said to be white? Austrian? European? Is it too popular, thereby suppressing or supplanting the work of women composers? Or gay composers? Or black composers? Or Chinese or Turkish? Is it too obviously masculine? Is it just too German? So many stupid questions.

These many stupid questions -- mine too -- are brought to us by the prevalent and inept application of stereotypical adjectives pretending to tell us something about various works of music and various makers of music, all the while revealing their own language conceit and through their application the conceit of the speaker. What is perhaps most amusing to me is that each of the newest application of stereotypical adjectives in fact shows us a marketplace strategy, rather more like capitalism than socialism, in which market share is sought by use of words -- advertising and public relations, if you will -- in which a product is supplanted by another product by changing the perception with words. With marketing. With social pressure. With politics.

Critic Bernard Holland offers an insight: "Music wears its illiteracy proudly, like a medal. I know this from my work as a music critic. I am helpless to write about what music is; I can only record the aftershocks it leaves behind." [ In "CLASSICAL VIEW: What's Easy on the Ears Can Be Painful to Describe," The New York Times, 16 November 1997 ] Given such truth telling by Stravinsky -- a member of that "dead-white-male canon" -- and a critic like Holland, these last decades' addiction to adjectives of national origin, race, gender and sexual orientation are examples of lazy thinking, at best, and competitive, name-calling politics at worst, telling so little about the music and even the texts to which music is so often set. Holland says music is illiterate, and that seems most true. It is only our time and a host of musicological Scheherazades busying themselves with adjective after adjective, identifying their underlying motives in the process thereof. Among their motives is to be noticed and of course to be paid.

Somehow, I suspect that this particular Zeitgeist will also pass, and then pass away.

Strozzi's output is not undervalued when compared to Puccini's mainstream operas in the repertoire today, though an application of the accusatory adjective would have us conclude something like this. Boulanger's opera omnia is not suppressed by reason of misogynist and sexist stances because Ravel's appeals more to a consuming public. Beethoven's canonic symphonic output does not overwhelm Boulez' based on the hegemony of heterosexuality over homosexuality. Wagner's great operas do not supplant Still's based on being white racist, and the consumers of classical opera should not be accused of being racist without such an accusation receiving intelligent and pointed ridicule. The use of such adjectives as become pejoratives through the nattering pens of today's musicological Zeitgeist as found in the arena of classical music is a sign of our times. But some music is what it is and has the value it does for reasons most musical, inaccessible to the fumbling adjectives and their now evident conceits.

And yet, this article began with Sheehy's quote -- the "dead-white-male canon."

Above, I mention Emily Ezust's fine yet condemned-to-be-ever-incomplete site, The Lied, Art Song, and Choral Texts Archive. As it grows as a database and reference for song texts identified in various ways, it currently lists over 13,000 composers and over 10,000 poets. More are added as the years pass. They are men and women, of many races and religions and nationalities and representing many language groups, of various sexual preferences, and the aggregate whole spans the most performed to the least performed. All arguments to the contrary, the "canon" is not as limited as silly socio-political bluster might have us believe, as represented by this useful database runs a gamut from composers of a single song to composers of hundreds, and from the almost unknown to household names within the classical world. Attaching adjectives to these creative individuals is an inexact social science at best, and a pejorative attack at worst with one consistent goal -- to suppress one class or group or individual in order to advocate for another. That is just brute level marketing.

The competition for attention in a population of over 13,000 composers is the game and gambit of this Zeitgeist today, and has made extra-musical careers for many opinion makers attempting to sway a public's attention from one to another based on adjectives aplenty telling us almost nothing about the music itself. It is the music itself which interests me greatly. I suspect I am rather like most of the consuming public, not swayed by the "oughts" of so many adjectives of such little persuasive power except to muddy, confuse and complain.

Scheherazade was a storied storyteller par excellence. Stories are made up of characters which become more alive as adjective after adjective pile up to flesh out a proper noun into a full-bodied image which acts with some clear goals as the drama -- be it tragedy or comedy -- unfolds.

Adjectives are of such evocative and narrative power that it is expected such force and function will carry over from mental domain to mental domain, but Stravinsky has reminded us that this is simply not so. Music is most difficult about which to speak, because speaking accomplished in language and music is another mental module of mind. Musicology is conducted in words, and not in music. It simply cannot, just as this prose of mine is not singing to someone reading it in the moment. A "new" musicology is more words, more adjectives, more conceits and target-specific goals than an older musicology. But time passes, and the "new" becomes orthodox, then rigid and old and ineffective, ready to be supplanted by the next "new" poised to dethrone it.

Our current and aging crop of musicological Scheherazades is becoming bent and crusty, as a next generation awaits its time to move into a coming but as yet not seen Zeitgeist which will declare today's "new" just something old, even historic. Even over.

I refuse the now "new" notion that there is a music which is of one demonstrable gender as opposed to another and that one is of better value than another based on a distinction of gender, or of one clear racial identity versus another and that one should be more prized than another based on racial perceptions, or of one socio-political truth versus a supposed lesser based on any of the above adjective-laden distinctions. I predict the changing Zeitgeist will look back upon this time rampant with socio-stereotypical adjectives to describe music and its music makers as intellectual claptrap, opposing academic prejudices and ineffective marketing strategies to bolster one product or set of products over another.

And I know this too. Only time will tell.

9 November 2012, Berlin

Copyright © 2012 Gary Bachlund All international rights reserved.

NOTES

[ 1 ] The notion of a canon of music by "dead white men" and other radical pronouncements have swept various writers on music. It is indeed amusing that as some men would learned devotion to the terminology age, they make connections. Prominent among the early radicals whose words came back to haunt is Pierre Boulez. One found:

"In 1971, composer and conductor Pierre Boulez declared 'all art of the past must be destroyed' '" was cited in Josh Rosen's The PIERRE BOULEZ Project, a performance art / mail art piece, now declared "over." In it in order to follow the radical statement of a young Boulez, Rosen saw to the "destruction of over 100 Pierre Boulez LPs, CDs, tapes and books occurred on Feburary 28, 2005 at the Church of the Friendly Ghost in Austin, Texas. The material was not simply destroyed, but used in a diverse array of creative methods of sound production by Rick Reed (turntable, electronics), Brent Fariss (turntable, electronics), Alex Keller (CD players, electronics, torch), Nick Hennies (recitation, snare drum) and Josh Ronsen (turntable, electronics, microwave oven, garden shears, mastered hammer, lighter, electric drill, movement). The result was a unique art event the world will never experience again. That night, the past was destroyed, the future ignored and the present focused upon amongst friends ready to embrace the world." Some were amused, and some aghast.

This footnote, added after writing the essay, tells a different yet related tale:

Roger Bourland writes of his own project of late: "There is an odd kind of necrophilia going on in the project. Reading, handling and listening to these old publications is slightly eery [sic]. Many of the artists who made this records are dead. The publications themselves are dead, although some have been digitized and brought back to life. Many of the companies that made these publications are long gone, as are the artists who designed the covers and the people who wrote the program notes." In "My old LPs," a blog post by Roger Bourland, 29 August 2013.

Perhaps as demographics and culture change and as the remnants of a sclerotic cultural Marxism now fade, a canon of "dead white women" will be conjured up by the next young radicals. Or perhaps "dead black men?" Or.... It really matters not in the long arch of history, because the value of works of art will be that they -- not the race, gender, sexual orientation or any other stereotype -- as works of art are preserved and revered by any group of people, as one sees today in those societies and foundations which dedicate their work to an artist's opera omnia. Over such free will actions, short-sighted politics had, has and will have no sway.